As far as mountain bike destinations go, Rock Springs and Green River, Wyoming sit in the middle of a bunch of them. Park City, Utah is two-and-a-half hours away. Jackson, Wyoming is 3 hours away, Fruita is 4.5 hours away, and Moab is six hours away.

Not many people would yet consider Southwest Wyoming as a mountain bike destination on its own, even though the trails are well-made and reminiscent of Western Colorado or Southwest Utah, with miles of flowy singletrack over dusty trails along mesa edges with drops and planks sprinkled throughout.

Down the road from Rock Springs in Green River lie enough miles of singletrack to justify a full day pitstop to spin out a heavy set of road trip legs, and the towns are eager to bolster their outdoor tourism potential.

Ahead of a drive from Denver to Park City, I got in touch with Brent Skorcz who helped found the Sweetwater Mountain Biking Association (SMBA), and he and a few others were kind enough to show me around the trails in Green River and talk about their history.

Skorcz founded the SMBA more than twenty years ago. After work, he’d hop on his bike and take off into the desert. This was around 1989, he says, and after a day in the mines, he needed an escape.

“I’d get off work – I was working 12-hour shifts, and then they’d be calling me out to work or they’d have something go down and they’d call me out and I thought, ‘I gotta get away from this place.’ It was just a good release to go out there. I rode by myself for years.” He started building Brent and Mike’s trail in the Green River area back then and slowly it’s evolved into a network of trails and Brent and Mike’s is now a blue-rated 6-mile loop with A and B-lines, and a smattering of other trails that surrounds it.

There had been a quasi-club before, but it was under the arm of the chamber of commerce and the association was confusing to others.

“We were just a sub-committee of the chamber basically,” says Skorcz. “We figured we need to get more people, and people weren’t interested in joining a trails group at the chamber, you know. They didn’t really understand what that was.”

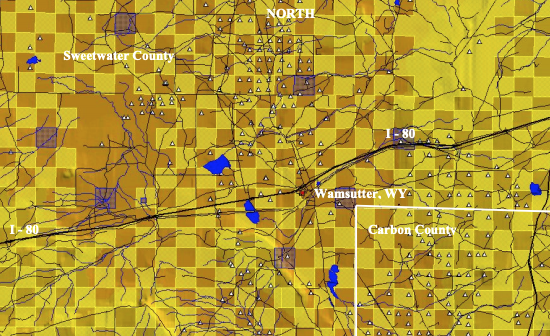

Skorcz went to an IMBA Summit in Park City in the mid-90s to learn a little bit more about mountain bike advocacy and navigating land management. This was an important one as the land ownership is unique around Green River and Rock Springs. Land all around both Wyoming cities is in a checkerboard pattern. Vast areas of land in southern Wyoming bounce back and forth between private and public, owned by either the Bureau of Land Management or private entities like Anadarko, Occidental Petroleum, or the Sweetwater Grazing Association.

When the transcontinental railroad was established in the mid 1800s, Congress established every other square mile of land in Wyoming within 20 miles of the railroad as either public or private, and eventually handed over mineral rights to private companies to encourage railroad building in the state.

Attending the IMBA Summit and establishing the area’s first mountain bike club gave Skorcz and others a better way to conversate with landowners about navigating the checkerboard, working with the city, and getting more kids interested in riding bikes. Skorcz says that often if kids can choose between a mountain bike or a dirt bike, they’ll pick one with a motor.

SMBA has centered around being a mountain bike club, rather than an advocacy arm for the area. SMBA hosts a trail day once a year at the Green River/Wilkins Peak trails, where they’ll clean up trash and conduct maintenance, and they’ll also host group rides or take trips to Fruita, Moab, or Park City. Throughout the year SMBA members will maintain the Wilkins Peak trails and build features as needed.

Skorcz says they have had a good relationship with both the BLM and the grazing association. The club has built a reputation of building trail responsibly and trying to keep singletrack single. Many of the other lands users in the area – ATVers, dirt bikers, and recreational shooters have had a reputation for mistreating the trails, the land, and trashing the Wilkins Peak area hence the cleanup days. Skorcz says the trash has gotten better recently.

The BLM gave the club a pile of trail markers that designate the trail as bike only, and non-motorized. They’re often found with bullet holes in them, or run over by side-by-sides. Skorcz says mountain biking can lead to a domino effect with other user groups in the area. A dirt biker will see a mountain biker on the trail and assume they can ride it since they’re on two wheels. An ATV rider will see a dirt biker on the trail and then assume the trail is for motorized use. The impact on the delicate desert soils is irreversible.

“Once it’s two-track you can’t change that,” says Skorcz.

Rock Springs new frontier

Skorcz notes that there are some trails in Rock Springs proper, but they are mostly unofficial, and the Wilkins Peak trails remain the only mapped and sanctioned trails around.

When Randall Dale moved to Rock Springs with his wife, who took a job at the local community college, he got in touch with some folks at the city to find out where he could mountain bike. Dale says, they basically told him to pick a dirt road and watch out for traffic. He thought that there must be a better way.

Dale started eyeing up the open space near the college and got in touch with the board. Since there were no plans for the land, he was approved to build a multi-use trail as long as it didn’t cost the college money. He laid out a plan for the trail and started recruiting volunteers. At about 3 miles, the college trail won’t be extensive, but it will be different.

“It’s right in the middle of town. That’s what’s exciting about it,” says Dale. He’s also building the trail at a 42-inch width, making it more accessible for adaptive users.

Since the dirt is like flour and turns to pudding in the rain, Dale prepped the trail with a road base mixture to give it a solid base. Sunroc, a local concrete, and aggregate supplier donated 300 tons of the road base.

“Anywhere the road base is down, it’s tough as concrete now,” he says.

The city of Rock Springs seems to be coming around to supporting outdoor recreation and utilizing new grants. Skorcz and Dale both mentioned they recently received information on new grants that may be available for outdoor recreation.

Dale is optimistic about new trails and the potential it brings to the county. He now heads up the Sweetwater Trails Alliance. He mentioned the possibility of a 26-mile loop on top of White Mountain, a mesa that curves between Green River and Rock Springs, and new funding and resources that may be available through the new Wyoming Office of Outdoor Recreation.

Dale asked the department about help with the trail layout at the college since he found that outside trail consultants can be very expensive. The Office sent someone from their team to help with the design and lent tools and expertise.

A support system for the outdoors

The Wyoming Office of Outdoor Recreation started in 2017 as elected officials and recreation stakeholders sought ways to enhance recreation opportunities and diversify Wyoming’s extraction-focused economy. There are subchapters of the outdoor recreation office across the state and they are all region or county-based. The Sweetwater County Outdoor Recreation Collaborative began this year.

“So Southwest Wyoming, specifically Sweetwater County, we wanted to go there because coal, oil, and gas have been big parts of their economy for a long time and of course there’s always some question about what the future of those industries holds. A lot of the factors in those industries that determine their health are either related to politics on a broader level or they are related to the local economy,” says Chris Floyd, manager of the state’s outdoor recreation office.

He describes the collaborative as a way to bring a diverse range of recreation interests to the table, including conservationists, elected officials, and recreation groups to get them talking about how to grow and manage recreation.

Maybe a county wants to bring more people in through tourism, or enhance current recreational opportunities, or improve the outdoor experience in an area. They’ll work with motorized users, non-motorized users, or anyone from firearms enthusiasts to rock climbers.

In Sweetwater County, the checkerboard system is still going to be a challenge.

“If it’s a large landowner or maybe a large grazing association or mining or an extraction company, a lot of times they’re okay with people who are just passing through, but you never know. As long as their property is being respected, they’re not typically too concerned with people just passing through,” says Floyd. “But still, if a trail crosses through the checkerboard, the private landowners have to be involved. I mean, they’re going to have to have a seat at the table.”

It also may depend on what he’d call disorganized recreation, say a casual group ride with friends, or organized recreation like a cross-country race. What may happen, is that the landowner requires the user group’s main organization, say SMBA or STA to take out an insurance policy, which is something Skorcz with SMBA has had to do before. These can eat up much of a club’s revenue.

What it seems like SCORC and the outdoor recreation office will provide are more channels for recreation advocates to enhance opportunities for adventure with the help of the state government. The establishment of SCORC and the outdoor recreation office is a progressive step for land that has historically been dedicated to commercial interests and as interest in recreation begins to drum louder, the tides just might turn.

As Floyd puts it, the collaborative is a “chance for Sweetwater County to be proactive because we know that the growth and recreation is coming regardless. There’s going to be more people coming to Sweetwater County or people recreating, there’s gonna be increased pressure on public lands, so whether we like it or not, it’s coming. It’s just, how do we address it?”

0 Comments