🗣 We love reader comments! Personal attacks go against our comment policy and Singletracks reserves the right to moderate community posts accordingly.

One of the ways we’re celebrating Black History Month around here is by talking with our BIPOC community members about what has and hasn’t changed in the bike industry following a period of racial reckoning spurred by the brutal killing of George Floyd on May 25th, 2020 at the hands of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. The horrific act, and Chauvin’s subsequent conviction on state murder charges, marks a key point on the civil rights timeline in the United States, followed by protests, boycotts, and a good deal of self-reflection and re-education.

Shortly after Floyd’s death, nearly everyone across the bike industry recognized that their brand or organization wasn’t part of the diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) solution, and many made vows to change that — Singletracks included. Black squares and statements of support for BIPOC communities covered any and all social media platforms with promises to do better, to create representation for Black riders in cycling, and to hire BIPOC employees who can make decisions that affect cycling culture more broadly. So what has changed and what still needs work? We sat down with Colorado-based mountain biker Brooke Goudy to get her perspective on that hefty question.

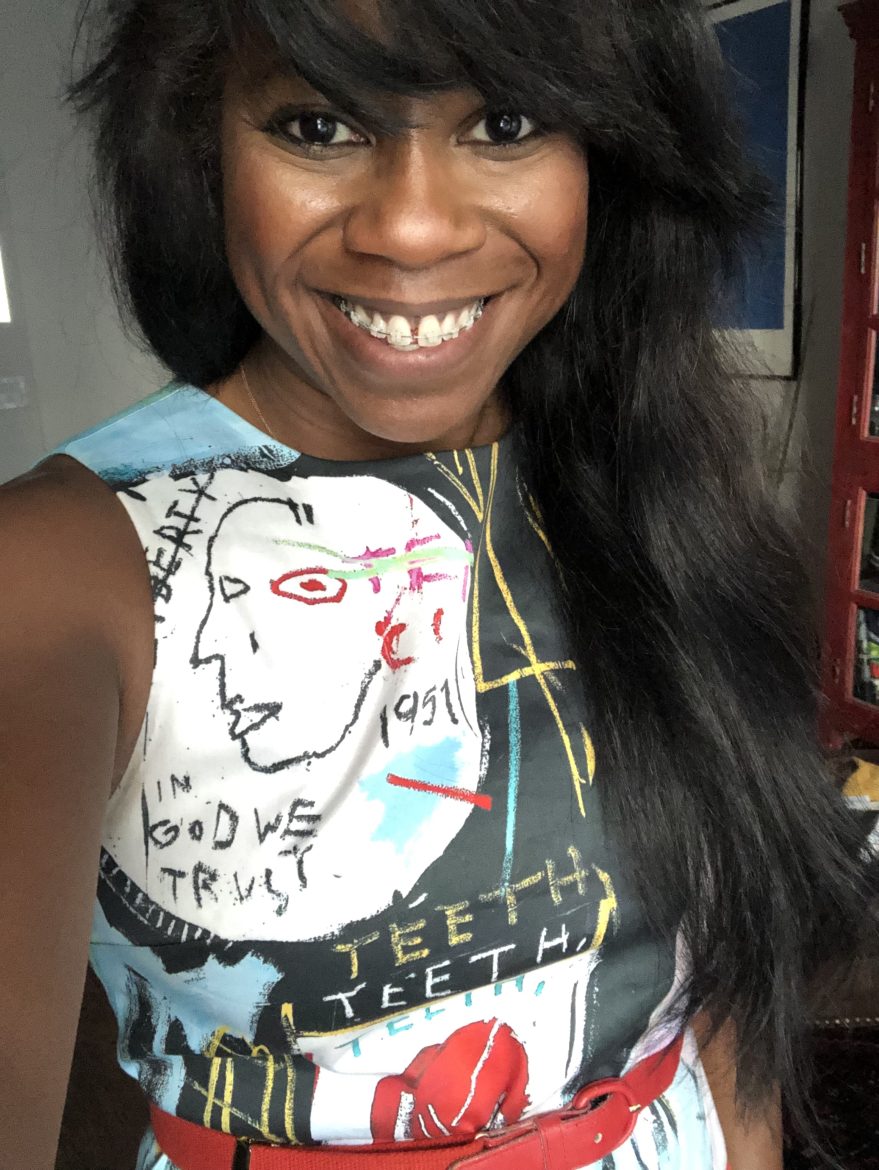

Goudy is a Black mountain bike athlete who lives in Boulder, Colorado, and works as a school nurse in Denver when she’s not training for the next epic bikepacking race. She also sits on the board of her local trail association and several other MTB organizations and leads Black Girls Do Bike events in her community.

In late May of 2020 when many of us awoke to the notion that we could be active participants in the civil rights movement, regardless of our race, Goudy saw hope in some of those messages. She had been working to welcome Black athletes in her community for many years prior and found the wellspring of these newly stated intentions to be a positive step. Long before the renewed social justice reckoning, she was asking the hard questions of “what is happening that we don’t see any people of color in cycling? What is happening that we hardly see any women in cycling? How welcoming are we? Is it because folks of color don’t want to be here, or is it because we are not inclusive enough, welcoming enough, or representative enough so that folks of color want to be here?”

Her efforts and energy come from a long lineage of civil rights leaders fighting for change. “I was doing all of the things that Black folks were doing before anyone was listening to them or supporting them.”

About that historically significant day in May, Goudy recalls “It was very emotional for everybody. White folks. Brown folks. Black folks. It was just a very emotional experience. I think everybody was reckoning with this idea ‘does racism exist?’ People were seriously asking themselves that question. Especially white folks who hadn’t before. I think that a lot of folks came to the conclusion that it does and asked, ‘what do I do now?’ And, there were a lot of voices that hadn’t been heard. That have been shouting and trying to get through all the muddy water, to the rest of the world. Finally, those voices were being uplifted and people were hearing them. From that grew this opportunity for voices to be heard that have been basically screaming and trying to get out there. It seemed that a lot of people were ready to listen. But at that point, what we wanted was action, and when I say we I mean folks of color. We had already been talking and by the time people were ready to listen we were ready for people to be called to action.”

Months after brands and people posted those black squares Goudy recalls seeing DEI statements appear from brands across the bike industry. In a clever twist, she began sending those Instagram posts to the companies that wrote them. When a few of them replied and asked why she had sent them their own mission statement she said “I want to remind you of your mission and that you put out a call to action. I just wanted to send you a check-in with your own words. What’s more powerful than your own words?” Goudy says it was hard to see if the companies were doing anything other than making a statement, and she wanted to make sure the companies making those statements knew that people are paying attention.

One of the ways Goudy has seen things change in the bike industry since May of 2020 is via representation in advertisements and marketing. This past summer she completed the Great Divide MTB Route, with its 2,700 miles and nearly 200k vertical feet. Goudy ran into very few women on the course, and most of her daily riding encounters were with white men. She was filled with excitement whenever she saw another woman on course, cheering them on for the win.

“I have to say it was really tough not seeing anyone that looked like me. It was tough going through white town after white town where I didn’t know how I was going to be treated and if I was welcome in that town. There were subtle things happening that let me know when I wasn’t welcome in those towns. Then, I got to Salida, [Colorado], just a tiny bit over halfway. I was a little beaten down. I’d say the Great Divide beats you down a little. I walked into this bike shop and they had Velo magazine, and on the cover was a Black woman bikepacker. I started crying. I took a picture of it. When I got back to my tent I stared at that picture and I was like ‘we’re supposed to be here. We’re meant to be here.’ That’s how much representation mattered. Whenever I got discouraged. Whenever I felt like I didn’t belong in those towns or I didn’t belong out there it felt good to pull out that picture. I carried the picture with me on the rest of the Divide. It was so amazing to see someone who looked like me on the cover of a major cycling magazine.”

On representation today, Goudy adds “Social media looks different. I’m seeing folks that look like me. I’m seeing an effort for people to make diversity a thing. Oftentimes I see it in the form of women more than I see people of color. I see it in the form of fewer elite riders, and more riders who are going out there and pushing their body like me. I’m no elite rider, but I go out there and I really challenge myself. To see the everyday person. To see the everyday woman. To see the everyday Black woman going out and doing things on their bike, where you only used to see certain types of people being able to do it. Only certain body types doing it. Only a certain color of people doing it. I think it’s important to show that.”

An important element of racing for Goudy is to push herself and do the hard stuff. “It’s good to know that I have that resilience, and that resilience sticks with me even off the trail and becomes part of me in my everyday life.”

In addition to pushing her body to the limit, Goudy wants to be out on track to show that people who look like her belong in the outdoors, belong in mountain biking, and that this sport she loves so dearly is as much hers as it is anyone else’s. She has a powerful way of talking about resilience and how she’s always had resilience. It’s an integral part of her heritage, and her ability to endure glowed during the massive Divide ride.

In addition to racing, Goudy will be touring with Roam Fest. She said that the folks running the women’s mountain bike festival are some of the best in the business at taking care of the people they work with.

“There’s not a time where I was talking with Ash [Roam founder Ash (Bocast) Zolton] where she’s asked me a question that she didn’t pay me for. She values women. She values Black women, and she values the consultations that I give to her. She’s listening to this new drumbeat of ‘pay black women.’ Don’t invite them in under the disguise of equity and inclusion to do all of this DEI work so that you don’t have to pay a consult. Pay them. And Ash is someone who stands by that. She’s an example of someone in a white organization who’s getting it right.”

For her own part in the industry, when Goudy runs a clinic for Black women she hires Black women to help out and pays them well. When she needs photographs taken at those events she hires a Black photographer and, again, pays them above the industry standard. Seeing one Black woman on the cover of a magazine filled her with joy and determination and she knows new riders at those events will have the best chance of feeling welcomed when they get to work with and be supported by people who look like them. From a purely economic standpoint, Goudy says, “I make sure that my money matches my words.”

Goudy said that she wants to see more BIPOC people getting seats at the table when decisions are made with advisory boards and policy groups. She is volunteering time and emotional labor all over the place to make spaces and events better for people of color. “If I’m not invited to the table, I’m bringing my folding chair to squeeze in and make room for myself at the table. Representation is important, but policy and breaking down long-term barriers are important too. Those tables are still full of white men.”

One question Goudy would like to ask all the mountain bike brands that posted DEI statements and black squares on social media is “does your company look like your ambassadorship? Does your company look like this new team you’ve just promoted and taken pictures of?” She wants to know if the people making decisions around who gets those sponsorships and ambassadorships are a diversified crowd. Are there employees with power at your organization who are people of color? If not, is your DEI statement authentic? Goudy also mentioned that when she meets with the folks in charge of various companies and organizations, the people in charge are almost always white men.

From the brands

We asked Goudy’s main sponsors, Pearl Izumi and Yeti Cycles, how their company culture and policies align with their DEI statement.

Pearl Izumi shared the following: “In 2018, we kicked off a brand initiative to focus on inclusivity and better represent diversity in our ambassadors and our marketing imagery. But the movement in the cycling community during the summer of 2020 reframed the challenge and the opportunity for our entire business. We’ve clarified our diversity goals in relation to photo and video content; specifically, that our model casting should represent the American population. We’ve built an even more diverse roster of athletes and ambassadors, which is currently 41% BIPOC. We’re also telling stories from riders with different backgrounds so that aspiring riders can see themselves as part of this community. We’ve used our Go Grants program to support groups that are doing great work to make cycling more inclusive and welcoming, such as Bikepacking Roots BIPOC Adventure Grant, Smiles 4 Miles, All Kids Bike school grants, Lucky to Ride program support, and High School MTB Team sponsorship, and The Underground Railroad Ride project and film.

“We’ve also taken steps to make job postings more visible to more communities and to ensure that our hiring process is welcoming to groups that are not well represented in the cycling industry. We’ve provided education to our employees on DEI topics. For example, our entire team is currently taking part in a multi-session course on unconscious bias. We have an internal committee that is focused on DEI, but really the company has infused diversity and inclusion into our everyday decision-making. We have plenty of more work to do, but we’re proud of the progress we’ve made.”

Yeti is similarly committed to change for the future: “There is an added focus to diversifying our staff, ambassador, and athlete rosters. We are also working to support our ambassadors and their work to diversify mountain biking. An example of this would be our work with Yeti ambassador Brooke Goudy. Her work with Black Girls Do Bike is key to diversifying our sport. Additionally, Yeti is a founding sponsor of the Grow Cycling Foundation through fundraising contests and donations. We still have a long way to go, but we’re in it for the long haul.”

When Goudy recently went to Yeti HQ to fetch her new bike she was greeted by a Black employee who was super stoked to meet her and chat about all of the exciting events she’s involved with. They spent some time sharing trail tales, as we do, and talking about the season to come. This interaction exemplified, once more, the power of seeing people who look like her in the mountain bike industry and culture.

This coming spring Goudy and two other BIPOC athletes will compete in a bikepacking race in Iceland which includes 590 miles of pedaling over four days, fully loaded. She received 33 applications for those two spots to join her in the race, followed by the trying task of selecting riders who are ready for such an adventure. Goudy says she’s riding as much as possible to prepare for the June event, though her race season kicks off even earlier with Mid-South in early March.

One final element Goudy would love to see in mountain bike culture is a diversity of voices being uplifted and celebrated, just as much as the “bro” culture voices are. Like many of us, she would like to see the negative comments drowned out by statements of how the brave work she and others are doing is important.

“I’m just wishing for more love bombs. Like an explosion of love bombs in those comment sections.”

2 Comments

Feb 23, 2022

Feb 23, 2022