Every couple of years, the bike industry latches onto a term or phrase that seems important for the time. How many years has “long, low, and slack” been floating around, and more importantly are there any mountain bikers who haven’t heard of it?

Marketing folks continuously describe suspension kinematics as having a “sensitive top stroke, supportive mid-stroke, and strong bottom out resistance.”

In carbon conversations, brands describe frames and wheels as “stiff, yet compliant,” which oddly enough aluminum seems to accomplish too, but let’s not go there.

These are all evolutions in geometry and technology that have made mountain bikes noticeably better year after year, and the point is not to get down on them. But these things can be hard to keep up with and also easily lost in translation. The result? Bike industry jargon washes over consumers like a pancake bathed in maple syrup and we’re all lost in the sauce.

The fork offset conversation certainly isn’t new, but talk is still raging on and it’s an important part of modern mountain bike geometry and new bike launches. With that in mind, here are the basics of fork offset and how it affects bike handling.

What is trail?

Trail is the distance between the contact patch of the tire — where the tire touches the ground — and the steering axis. With a bigger wheel size, there is more trail, since the axle is higher, creating more distance between the contact patch and steering axis. Naturally, there will be more trail on 29ers than 27.5-inch-wheeled bikes.

With increased trail, you get a more stable feeling bike. The tradeoff, however, is that bikes with more trail take more steering input to respond. This isn’t a bad thing. With how fast enduro bikes are being ridden these days, who wants a bike with sharp steering at 30mph on a high speed jump trail?

With less trail, the opposite is true, resulting in faster steering and a more agile bike. XC riders are typically on tighter trails, where slow speed handling becomes more important. Cross-country racers don’t want sluggish steering when they’re trying to pass other racers in tight places.

What is fork offset?

Fork offset — also known as rake — is the distance between the axle and a straight line through the head head tube. Offsetting the fork more (increasing offset) pushes the axle further in front of the head angle. Reducing the offset — which is what many bike designers are doing today — pulls the axle closer. This has two effects.

With a reduced offset — and in today’s terms we’re talking about offsets between 37mm to 46mm — it increases the amount of trail, because the wheel will contact the ground more ahead of the steering axis. Why is this important? If the introduction has escaped memory already, it’s because bikes have gotten longer and slacker. With slacker head angles and a longer reach, top tube, and wheel base, the front wheel has been pushed further in front of bikes and created slower steering responses.

By reducing the fork rake (offset), the head angle remains the same for stability at high speed and down steep and rough trails, but the wheel is closer to the steering axis for better handling, especially at slower speeds. With everything longer and slacker, bikes shouldn’t feel bus-like when we’re riding up switchbacks to the top of the climb.

So if a slacker head angle means that a bike will have more trail, and reducing the offset means more trail, why do engineers make slack bikes with reduced offset forks? By the end of the conversation, it sounds like there’d be enough trail for a bikepacking race. Well, reducing the offset brings the axle closer to the rider and more directly under the rider’s weight to better translate steering input.

Offset preferences for head angles and wheel sizes

Trail changes depending on how steep or slack a head angle is. With a steeper head angle, the amount of trail is reduced, and with a slacker head angle, the amount of trail is increased. If we think about what kind of bikes see a steeper head angle and a slacker head angle, it all kind of makes sense. As mentioned above, steeper angled bikes are typically made for slower speeds and agility already. Think of how different an XC bike handles from an enduro bike, which is meant for steep or high speed trails when stability is preferred over the ability turn more sharply at slower speeds.

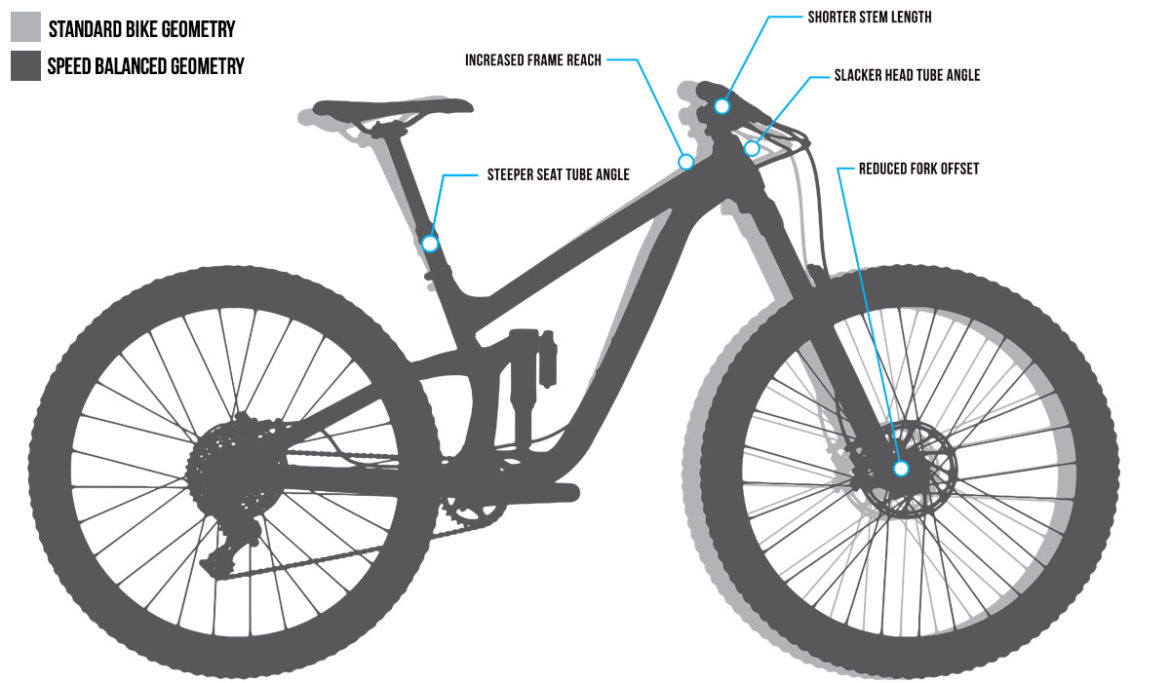

Also as noted, most mountain bikes are slacker than they were years ago, and get a little slacker every year, including cross-country bikes. When the reduced offset movement started years ago, Transition basically initiated it by trying reduced fork offsets on slack bikes as part of their Speed Balanced Geometry.

It seemed like offset would be specific to wheelsize, with 29ers dealt a longer offset, and 27.5-inch bikes dealt a shorter offset, but now that long-travel niners have dominated the enduro market, the reduced offset is up for interpretation.

Bikes like the Transition Sentinel (of course) spec a reduced 43mm offset. The 162mm travel Pivot Firebird 29 and Yeti SB150 debuted last year are sold with a 44mm offset.

Another interesting bike to mention is the 27.5+ Whyte 901. The hardtail has a 64.5-deg. head angle, and a very short 37mm fork offset to compensate how far the wheel is in front of the bike.

Others like the Trek Slash and Devinci Spartan 29 have maintained a 51mm offset on their builds. Maybe this will change over catalog years with certain model years, but engineers and test riders are likely trying new bikes with different offset options to see what works best.

Aftermarket availability

Still itching to try something a little different or play with options? It might be expensive, but if you’re really into fine tuning ride feel and geometry, there are aftermarket options. Most brands tend to stick with the usual 44 and 51mm offsets, but there are some outliers. Fox offers a 37mm offset on its 36 Factory fork, but only on a 26 or 27.5-inch wheel size. RockShox offers 37mm offsets for 27.5-inch wheels also.

Others like MRP offer their 29er forks in 41mm, 46mm, and 51mm offsets. MRP’s long-travel 27.5-inch forks go down to 39mm, and also come in a 44mm offset. Cane Creek offers their forks in the two “standard” offsets, 44mm and 51mm.

Conclusion

Things move fast in the world of bicycle engineering and the fork offset conversation has grown tremendously over the past few years. While it’s not something any of us need to rush out and buy a new fork for, it’s nice to know what engineers and developers are thinking when they spec a 51mm offset fork on a bike versus a 44mm and vice versa. Rather than something that will make or break a bike, like many other component selections, it’s something that will enhance the ride and make it as capable as possible.

5 Comments

Jul 15, 2019

Jul 15, 2019

Jul 15, 2019

Jul 15, 2019

Jul 20, 2019

enter overly wide handlebars to handle the beast,

as an example some of these slack bikes are pretty much unrideable on semi-packed snow, with their self-steering undulating right and left until you get a halt.

to decrease otb, which these long front ends are all about, its better to just make the frame longer, and decrease stem accordingly. if you then would wish to increase stability, increasing trail is a better option than decreasing head angle.