Emily Greaves looks like a person who has her life together. She’s ex-military, speaks her mind without hesitation, and has a laugh like a car alarm. If you were looking around a sinking ship for someone who might know where the life rafts are, she’d probably be your first choice.

So when she tells me about a friend who took his own life and begins to tear up at the memory, it’s an unexpectedly affecting moment and one that makes the story of Greaves’ work even more fascinating to learn.

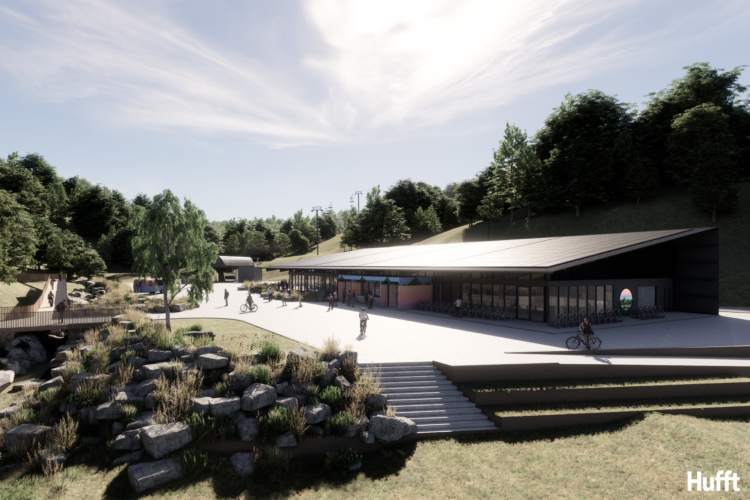

Comrie Croft

Greaves is part of the mountain bike skills and coaching team at Comrie Croft in Scotland. It’s a set of trails on private land that feels a world away from the publicly-funded forestry facilities found elsewhere in the country. No brisk committee-approved signage. No digital parking meters or state-mandated fencing.

This cozy, homespun enclave boasts over 21km of purpose-built trails ranging from family-friendly blues to some seriously technical blacks, with a skills area, a full-service bike shop, and coached or guided rides for individuals and groups. You can also eat excellent organic food; shop at a well-stocked store that carries everything from vegan chocolate to locally-knitted hats; camp in your vehicle, your tent, or one of their Norwegian katas; take a sauna… you can even get married here. It feels very much like a reflection of the way Greaves and her husband feel about their fellow riders and outdoor enthusiasts. It’s warm, friendly, and clearly a labor of love.

Which is perhaps why this place, and Greaves, were the first choice for the beginning of a unique mental health experiment — one that puts mountain biking at its heart.

Head set

As riders, we all know that getting out on our bikes is good for our minds as well as our bodies. An argument at home, a hard day at work, a problem that needs a bit of space and time? We go for a ride. It doesn’t make problems go away, but a combination of adrenaline, fresh air, exposure to nature, and the singular focus it takes to navigate trails has a way of putting those problems into perspective.

It turns out this vague, often-unspoken mental uplift is real — so real that it’s inspired Scottish riders, mental health professionals, and academics to create a program that prescribes mountain biking as therapy. Greaves is one of the first mountain bike guides and coaches in Scotland to be trained as a Trail Therapy practitioner, and local patients can now self-refer or have the program recommended by doctors, nurses, and mental health practitioners. If you get a place, you’ll get a real mountain bike to ride from the rental fleet, be taught how to use it, then be taken out with a group of other riders, two hours a week, for eight weeks.

All paid for by the Scottish National Health Service.

We’ve reported on this program before, back in 2019 and 2021 — its launch, how it was funded, etc. — but recently, we got a chance to spend some real time with Greaves on the trails, talk about her experiences delivering this therapy to real people, and ask what she thinks is happening in the heads of the people she rides with.

Risk is rewarding

We all know that mountain biking is risky — it’s why we do it. The rush from defying warning signals from our brains and bodies is palpable. It’s this powerful physical and mental reaction to risk that’s at the heart of the Trail Therapy project, and Greaves is keen to stress the specific benefits of riding at risk, as opposed to just being outdoors or exercising in general.

Greaves believes that trail riding’s therapeutic magic is found in the little moments — the stuff that literally flies right by as we’re riding. “This therapy needs to be actual mountain biking, not just riding a bike, because of the challenging aspects of actually doing real trail features,” said Greaves. In other words, it has to be a genuinely “risky” outdoor ride if it’s going to make any real difference.

Most of us take those moments of risk for granted — we don’t think too much about what’s happening. So it’s useful to approach the therapeutic benefits of risky features like we’re watching a skills video and break down what’s happening step by step:

- When we ride up to a challenging feature like a drop or a steep roll, our brains and bodies begin to react.

- We anticipate danger, we experience fear, and our systems flood with adrenaline, cortisol, and a host of other chemicals associated with stress as the brain and body work at lightning speed to decide what to do.

- If we’re experienced riders and we’re confident in our skills, we use our bodies to navigate that feature and keep rolling. That intensely pleasurable rush that comes right after pulling off a tricky move is that same warning system rewarding us for, essentially, feeling the fear and doing it anyway.

That process is proving to be an excellent method for helping people with mental health issues. Learning to ride a mountain bike on a real trail, with all the bumps, drops, rocks, and rolls that entails, strengthens their ability to recognize, face, and overcome stressful feelings.

In fact, Greaves is convinced that deliberately choosing, facing, and managing technical trail features is at the heart of why Trail Therapy works. “It’s really important to have that fear. Because then we can manage their cortisol, and do breathing exercises to calm down, and get to a place where they can ride a feature,” said Greaves. “The hit of dopamine afterwards is visible — you get to the bottom of an amazing trail, and you’ve loved it, and everyone’s high vibing, you’re up. And that’s that feeling that everybody gets.”

Unlike talk therapy or medication, being out on a mountain bike trail and facing frequent moments of challenge forces the body and mind to work together to overcome fear, and participants experience strong positive feelings as a result. That exposure to risk gives participants like Corie Davis* both the mental and physical tools to face similar feelings in other aspects of life. She’s been using the lessons she’s learned on the trail in ways she never expected.

“The emotional regulation… the decision making… it helps,” said Davis. “When you’re stressed, or scared… you can transfer that to going for a job interview or phoning the gas company or whatever you need to do.”

Doing the work

This isn’t just a whimsical experiment. The Trail Therapy program in Scotland is a result of Occupational Therapist Niamh Allen — herself a keen rider — being convinced that riding bikes on mountains would have tangible benefits for all kinds of mental health issues and working with Developing Mountain Biking in Scotland and other local stakeholders to find the funding to train Greaves and her colleague Scott Murray to be some of the first official practitioners. Since the program began in 2018, inquiries have been coming in from around the world. It’s cheaper than individual therapy sessions, it makes use of existing trail resources during quieter weekdays, and it doesn’t compete with or counteract any other therapy people might be receiving: counseling, drug treatment, or anything else.

It’s all worth it.

Greaves emphasized that a huge amount of the benefit she’s seen comes from the groups themselves. She’s watched them bond over the stress and success of tackling scary features and build mutual support over those shared weeks. Groups sign up for two hours a week on loaner bikes but often end up riding for way longer, showing up on week three with bikes they’ve bought themselves, or organizing bigger and longer rides without her help.

Greaves is the last person in the world to seek out any credit for the work she’s doing. But she does make a point of mentioning an intimate conversation with John Hollingdon — an early participant and cheerleader for the program — as one of her most treasured memories of working on the project:

“He said that trail therapy had done more for him than any medical intervention, any tablet, anything else he’d tried. It’s incredibly important to me, because my friend Gareth killed himself two years ago, and it was horrific. I said that if I can stop another person from doing that… John looked at me and said, ‘You have.’”

* Some names have been changed to protect the anonymity of participants.

2 Comments

Dec 25, 2024

I can vouch for the therapeutic value of my EnduroBMXPlus bike's therapeutic value value. Receiving a cancer diagnosis, mic fell through the floor. I was diagnosed with a bloodborne variety of cancer through genetic marker in routine blood workups. It hadn't set up housekeeping yet however, it was already in the works. My singlespeed RSD Middlechild, known as Sunspot was there and created the best of times. Going through treatment, on a good day, I would go out and ride my bike, albeit, it wasn't the session of all times, it was a mild pace with a few mundane moves. That was enough to make it a great session, for someone on chemo. Love the hell outta that Punkass bike!!

I have to say, bikes and the game of bike have untold healing powers, above anyone's expectations. Thanks for the article.

Dec 30, 2024