Mountain bike wheels are expensive, and there are a lot of things to consider when choosing a new set, or comparing builds. There are dimensions to be considered, and whether the rims are carbon or aluminum. Once that has been sorted, the question usually turns to hub engagement: how fast does the rear hub engage? To many riders, myself included, the engagement angle is seen as a proxy for hub quality and performance, though, as I learned recently, it’s not that simple.

To understand mountain bike hub engagement, I spoke with representatives from DT Swiss, Industry Nine, and Onyx, and experts involved in World Cup level racing, to understand the advantages and disadvantages of high engagement hub designs.

MTB hub engagement explained

All* mountain bikes make use of what’s known as a freewheel hub. Essentially, a freewheel hub propels the wheel forward when you pedal and also allows you to stop pedaling and “coast” without having to spin the pedals or cassette. There are a few different designs that make this possible, starting with a ratchet hub.

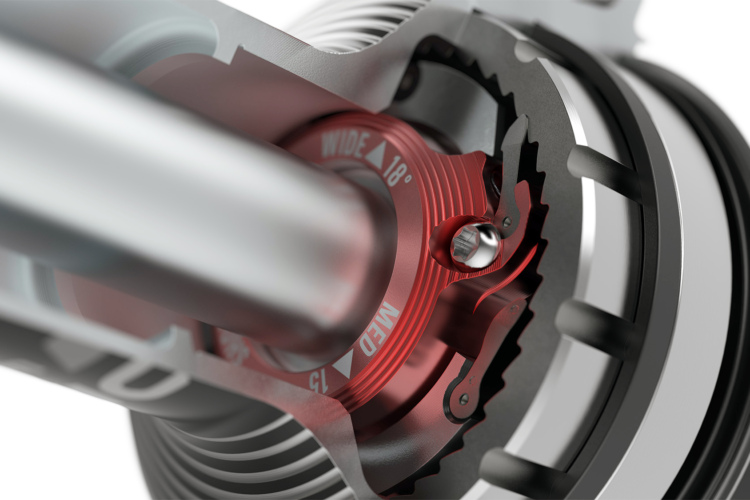

DT Swiss uses a design known as a star ratchet system. The ratchet is fully engaged along the entire surface area while pedaling, and springs allow the teeth to disengage for coasting. The angle of engagement for a ratchet-style hub is easy to calculate: divide 360° by the number of teeth. So, for example, a 36T hub engages within 10° of pedal rotation.

Before moving on to the other designs, it’s important to note that the actual amount of rotation required before a toothed hub engages varies each time you begin to pedal. Sometimes, the teeth are almost perfectly aligned and engagement is nearly instant; other times, they are at the maximum distance apart, and you’ll need to rotate the pedals until the hub engages. So, in the 10° example above, that’s the maximum amount of rotation required for engagement. In practice, it’ll take between 0° and 10°, and the average rotation should end up somewhere around 5°.

Another popular hub design, like the one used by Industry Nine, relies on a set of pawls that engage with an outer ring of teeth in the forward direction and are allowed to slip in the reverse direction. By phasing the pawls so that only one is engaged at a time, you can effectively multiply the number of engagement points. The illustration above lays out the math.

A sprag clutch design, which is less common, eliminates machined teeth altogether, using specially shaped sprags that are designed to engage with the walls of a smooth cylinder (no teeth) when power is applied in the forward direction. The sprags disengage when coasting or back-pedaling. With this design, the number of points of engagement is infinite, and the engagement angle is zero. Onyx holds a US patent that covers sprag clutch application to bicycle hubs, and the design was first applied to BMX hubs before being extended to hubs for mountain, road, and gravel bikes.

Advantages to high engagement hubs

Instant or nearly instant mountain bike hub engagement is desirable, particularly when it comes to technical riding. Jacob McGahey, Vice President at Industry Nine, explains there is “a benefit that you get from high engagement, particularly on technical climbing. You look at your average trail rider, the difference between cleaning and not cleaning a climb can often be that quick ratchet move.” Technical trail features, like rocks, logs, and roots require both power and precise pedal placement, which is why quick and consistent engagement is helpful.

Onyx General Manager Daniel Orellana says their high engagement mountain bike hubs are especially popular among certain types of riders. “The vast majority of our sales on the mountain bike side seem to be toward the trail and all-mountain usage, like enduro-type riders.”

Cross-country and gravel riders surely benefit from faster hub engagement too, though the advantage isn’t as clear for purely downhill riding where not a lot of pedaling is required. In fact, there are actually some disadvantages to high engagement, particularly when it comes to descending.

High engagement hubs and pedal kickback

DT Swiss has been especially vocal about how instant and near-instant engagement hubs negatively impact certain full suspension bikes, depending on the bike’s kinematic. Friso Lorscheider, Mountain Bike Marketing Manager for DT Swiss, notes that riders may experience more pedal kickback when running higher engagement hubs.

“With a full suspension bike, when the rear suspension moves into the travel, that means that the distance between the rear axle and the bottom bracket will change, and usually it’s getting longer. That means the chain starts to turn your pedals backward, and that results in kickback. At the same time, if the rider pushes forward, the rear suspension will not work [as intended].”

The DT Swiss website goes into extensive detail to show how backlash and pedal kickback interact.

McGahey from Industry Nine concedes high engagement can affect a mountain bike’s suspension performance, but only in very specific situations.

“In theory, it would be kind of a really low-speed drop or something like that,” he said. Or, “if you’re skidding down the trail and your wheels are not spinning at all.” Most riders, he notes, aren’t spending a lot of time with their rear wheel locked up.

Professional downhill racer and Frameworks team leader Neko Mulally says running an Ochain device — which allows between six and 12 degrees of chainring rotation — makes pedal kickback a moot point.

“We use an Ochain most of the time, so the engagement isn’t really any concern for us,” he told me. “For DH, we are more interested in low drag, reliability, and serviceability than engagement.”

McGahey notes that for riders running an Ochain, a high engagement hub delivers more consistent engagement for those times when you do need to pedal.

The other costs of engagement

As with everything in life and bicycles, trade-offs are necessary, and more is not always more. Pursuing ever more points of engagement impacts everything from durability and weight to cost and complexity, and may even affect drag.

Smaller teeth aren’t as strong

Lorscheider notes that the smaller the teeth, whether in a ratchet or pawl system, the more concentrated the load. There are “higher loads on the tips [of the teeth] because those ratchet teeth are getting smaller.” He notes that if loads become too high, this can lead to material destruction and higher failure rates. Therefore, there is a minimum tooth size that can be used.

The freewheel system “is a very critical thing when it comes to the function. If it fails, it’s not just that you cannot ride any longer,” says Lorscheider. “If it’s on an uphill section, it could lead to [injury].”

So, given a minimum tooth size, a larger diameter hub is necessary to fit more teeth for faster engagement. But as the hub gets larger, it also gets heavier, which is a trade-off many, especially cross-country riders, are unwilling to make. Orellana from Onyx admits their large, instant-engagement hubs tend to be heavier than other designs. “Our XC, road, and gravel guys, their main complaint is the weight.”

Race mechanic Brad Copeland says one of the teams he worked with several years ago tried higher engagement hubs but ran into problems. “We stripped out so many of them that we decided as a team to abandon using them altogether and swapped all wheelsets back to the old version with lower engagement.”

While DT Swiss has found 54-tooth ratchets to be the limit for maximum engagement and acceptable strength, brands like Industry Nine carve as many as 106 teeth into their drive ring using expensive wire-cut EDM machines.

More engagement = more dollars

OK, so that headline oversimplifies things a bit, but it’s clear that higher engagement hubs cost more, and much of the increase comes down to the cost of materials and machining. While no one I spoke with could speak to cost comparisons between different hub designs, pawl hub designs, like those used by Industry Nine, are complex systems that require precision-machined parts to function.

When I asked Orellana about Onyx’s patented sprag clutch design, he told me “patents are only as good as much as you’re willing to defend them. Our best protection on the product is simply how hard it is to manufacture.”

Beyond production challenges, Lorscheider noted that DT Swiss engineers found that moving from 18-tooth to 36-tooth to 54-tooth designs resulted in higher maintenance requirements. “With getting higher and higher engagement, the more service those hubs would need.” He says this is especially true for mountain bikes, “where you have all these interactions with dust, with mud, with water pressure washers.”

Hub drag can be a drag

Based on my research, it isn’t clear if there is a direct relationship between the number of points of engagement and drag. Lorscheider says, “the higher the engagement […] the more internal drag usually the hub will create.” Orellana begs to differ.

“Ratchet [designs] typically come with a lot of drag,” he said. “Sprag kind of checks those two boxes, where it has the highest engagement and it has low drag.”

McGahey, for his part, doesn’t claim pawl designs offer the lowest drag, but he notes there are many factors that can influence the effect.

“Your freehub seal design is actually where a decent amount of drag comes from on a lot of hub designs,” he said. And in a pawl system, drag can be influenced by “the angle that engages with the teeth, as well as your spring pressure on the pawls and also the depths of the teeth on your drivers.”

Mechanic Copeland notes that drag is a real concern at the highest levels of XC race competition, especially with multi-pawl hubs. “Some people have opted to run half the pawls, so engagement was less instant, but drag was reduced.”

So what does all of this mean for regular trail riders like us? Clearly, focusing on points of engagement alone doesn’t tell the whole story, and judging by the results of the survey below, riders are split over how much engagement they actually need. Lorscheider sums it up best.

Hub engagement is “not good or bad. It’s not black or white,” he says. “It depends on the customer.”

* Yes, fixed-gear mountain bikes do exist, but they are rare and are of limited utility.

21 Comments

Sep 5, 2024

Sep 5, 2024

Sep 5, 2024

However, you can easily tell when you don't have engagement when you need it while ratcheting up a technical climb.

Personally, I'll take the high engagement based on these factors. However, I found the discussion of increased drag and the potential for increased maintenance for high engagement hubs to be factors I hadn't really considered before.

Sep 9, 2024

Jul 7, 2024

Jul 11, 2024

It depends on the discipline, the rider, the terrain, etc. It depends on the bike, and the other technology available to the rider on that bike, etc. Etc, etc, etc.

Jul 7, 2024

Jul 7, 2024

It baffles me why anyone wants a pawled-up. Such fragile bits of metal hold all the power. Hydra hubs with insane POE and an axle as a consumable part are just plain dumb.

Jul 7, 2024

Jul 8, 2024

I ride a lot of lower speed Rocky ‘tech’ and hub engagement isn’t usually the problem if I can’t clean a feature.

I agree that the cost NOISE snd reliability of some high engagement hubs is a turnoff. (I’d like to try Onyx Vesper though, the silent hub is appealing as is ‘soft’ instant engagement)..

Jul 9, 2024

Jul 12, 2024

Jul 8, 2024

Jul 10, 2024

Sep 5, 2024

Sep 9, 2024

Jul 13, 2024

All advantageous from my perspective. What’s not to like?

I’m told, ad nausium, that 36 is the sweet spot for suspension action. Being a trusting guy, I’d go to that next time I need an upgrade. (Not backwards from 54, but if I bought another bike with 18)

Sep 16, 2024

Sep 5, 2024

Sep 5, 2024

Sep 9, 2024