The second generation Fox Live Valve suspension system launches today, and it comes with the codename: Neo. Live Valve is the brand’s electronically controlled suspension system, designed to automatically adjust damper settings so you don’t have to.

The first iteration of Live Valve, released in 2018, used wires to connect the pieces of the system, with includes front and rear bump sensors, an electronic fork damper, a shock damper, and a battery. Since these pieces were all connected by wires, it was quite the messy affair, and frames had to be designed with Live Valve in mind. It was a cool piece of innovation, but it’s fair to say that it didn’t really take off.

Going head to head with Rockshox Flight Attendant wireless suspension, Fox is going wireless with Live Valve Neo.

What is Live Valve Neo?

Neo is Fox’s own proprietary wireless protocol. Fox says that instead of using Bluetooth, which can have up to a 200 millisecond latency delay, the Neo protocol strips away all non-essential functions in favor of speed, delivering signals from the sensors to the controller in around one millisecond.

The Live Valve System

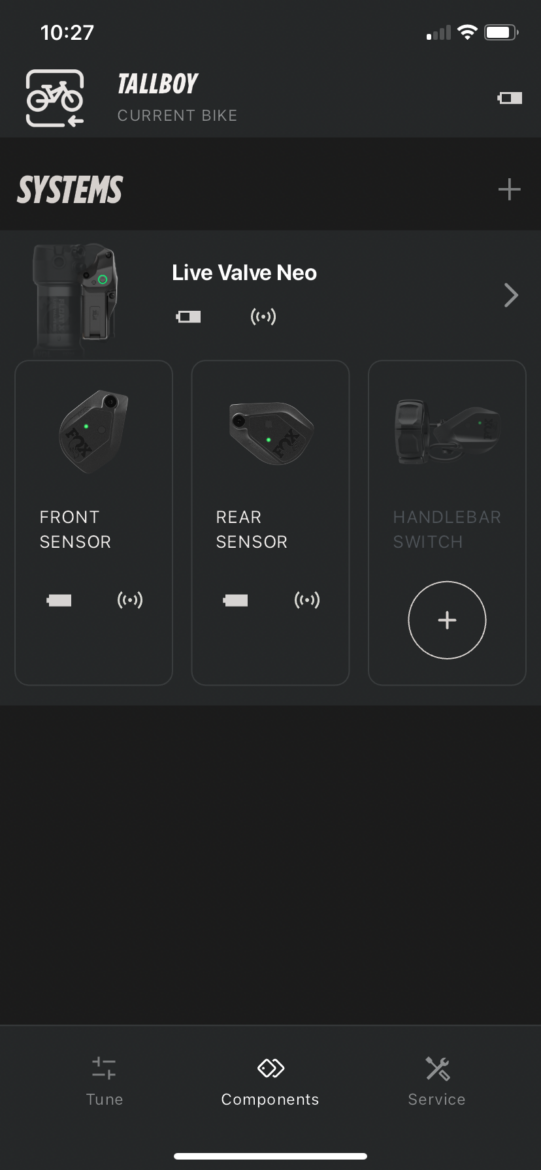

Fox Live Valve Neo consists of four main components, and a fork is not one of them, surprisingly. Those four components are:

- Controller for the shock

- Fork sensor

- Rear sensor

- Neo app

Bonus:

- Handlebar Switch (not yet available)

Neo differs from other electronically controlled suspension systems like Rockshox Flight Attendant in that the bump sensors are not part of the fork/shock, and are mounted at the brake caliper. This should in theory ensure the data coming from the sensors is pretty accurate to the terrain since they’re totally unsprung and undamped.

Fox says they deliberately did not include a fork as a part of the Live Valve system, since the majority of on-trail efficiency is derived from the shock, and any delay in the fork reactivity would be noticeable to riders.

Also included in the box is a rechargeable battery and charger. The battery pops out of the shock with a small plastic latch and is charged in its dock via the supplied USB-C cable. The bump sensors use standard coin cell batteries.

How Live Valve Neo works

Live Valve Neo essentially just switches between Open mode and Firm mode, depending on the way you’ve set it up, and the way it reads the terrain as you ride it. The bump sensors on the front and rear brakes transmit a signal to the shock when it should open and close, and that’s pretty much it. From a top-level view, it’s pretty basic, but once you get into it there’s a lot more subtle nuance involved.

The rear sensor detects bump force only, the front detects bump force and terrain angle. When the sensors determine that the damper should open, they send a signal and the shock opens. Fox says this signal can be sent in as little as one millisecond, and the switch between Firm/Open happens in as little as 1/70th of a second. The default position for the shock is Firm, so after a predetermined time, the damper firms up again, the idea being that it’s maximizing efficiency on trail. Oh, and for anyone wondering, should a battery die or a sensor disconnect, Open mode is the default with no power present, leaving it behaving like a regular Float X/DHX without a climb switch.

The open/close switch is activated by a magnetic latching solenoid, which they say is “faster than a motor while remaining virtually silent.” I would assume there’s less to go wrong here as well.

Fox says the idea of Live Valve Neo is that it gives the rider extra efficiency when it matters the most, not just on climbs, but also on the flats and descents. For example, it can firm up for extra speed when pumping, but opens when it detects a significant-enough bump. It can firm up for the takeoff of a jump, but opens for the landing. It’s also open for short technical sections during a climb when a manually locked shock would otherwise stay locked and lose traction.

Fox decided to only use “open” and “firm” modes and omitted a third “pedal” mode because of the speed with which Live Valve Neo can switch between the two modes. This negates the need for a middle-ground setting.

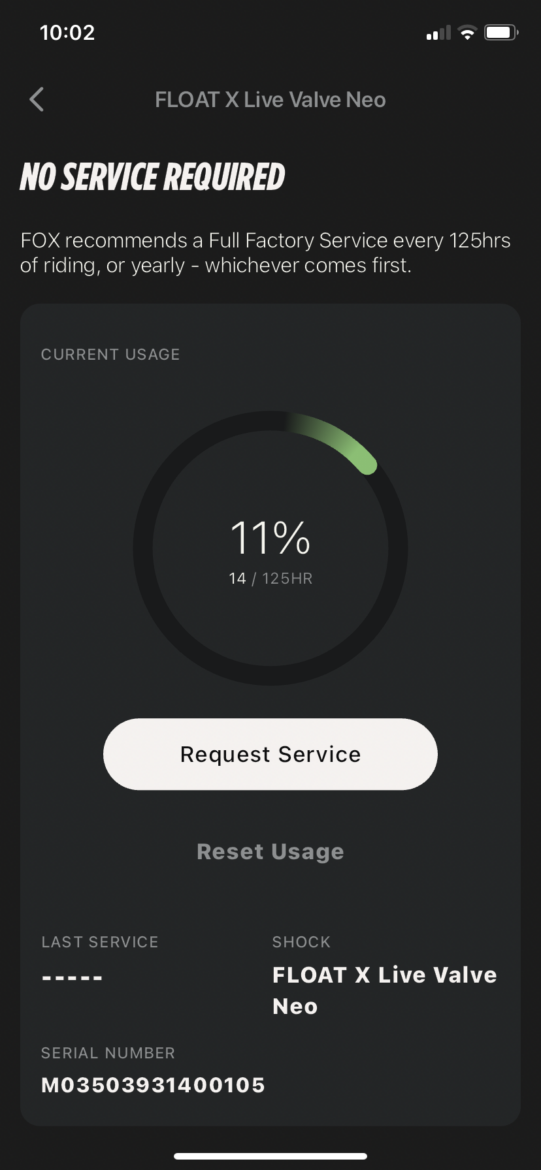

The Shock

Fox Live Valve Neo is available attached to either a DHX coil or a Float X shock, which is on test here. The shock architecture is based on the standard Float X and DHX, with obvious differences. Both are available in most of the common eyelet and trunnion mount standards, (190x45mm tested) and can have stroke reduced in 2.5mm increments up to 7.5mm. The shocks also share the same volume spacers as the regular Float X. Both have a 125-hour service interval, which can be tracked via the Neo app. The Float X is available in Factory spec only for aftermarket, and both Factory and Performance Elite for OEM. The DHX comes in Factory spec only.

Let’s talk weight quickly. Yes, Live Valve Neo is heavier than not having it. My sample shock alone weighs 583g, and 661g including the bump sensors. For reference, the Rockshox Super Deluxe Ultimate it replaced weighed 473g.

Install and setup

Installation of the Fox Live Valve Neo Float X shock was pretty straightforward. The shock fits like normal with regular hardware, though the piggyback is a little on the chunky side, so it’s worth cycling it without any air to check that nothing contacts under full compression. I installed the system on my Santa Cruz Tallboy.

The bump sensors are also easy to install — they simply fit on top of the caliper on the forward-most bolt on each brake. Fox supplies them with slightly longer bolts so they should fit most setups with modern brakes. It should be noted that the sensors don’t work with all calipers however, notably Shimano XT M8000. All said and done, the setup looks minimally intrusive, especially when compared to the old Live Valve system. So far nobody on the trail has even noticed that I’m running anything unusual.

Setting up the shock sag is done as normal, using a measuring tape, a shock pump, and the O-ring. There’s nothing special here, though you’ll want to make sure the shock is in open mode while doing so. Once sag is set, there’s a rebound knob in exactly the same spot as the regular shock; set as normal, based on air pressure and preference. The two final dials are “Firm mode tune” and low speed compression. The Firm mode tune allows you to tune the exact firmness of Firm mode, and has quite a wide range. Low speed compression allows you to tune exactly that when the shock is in Open mode.

Neo App

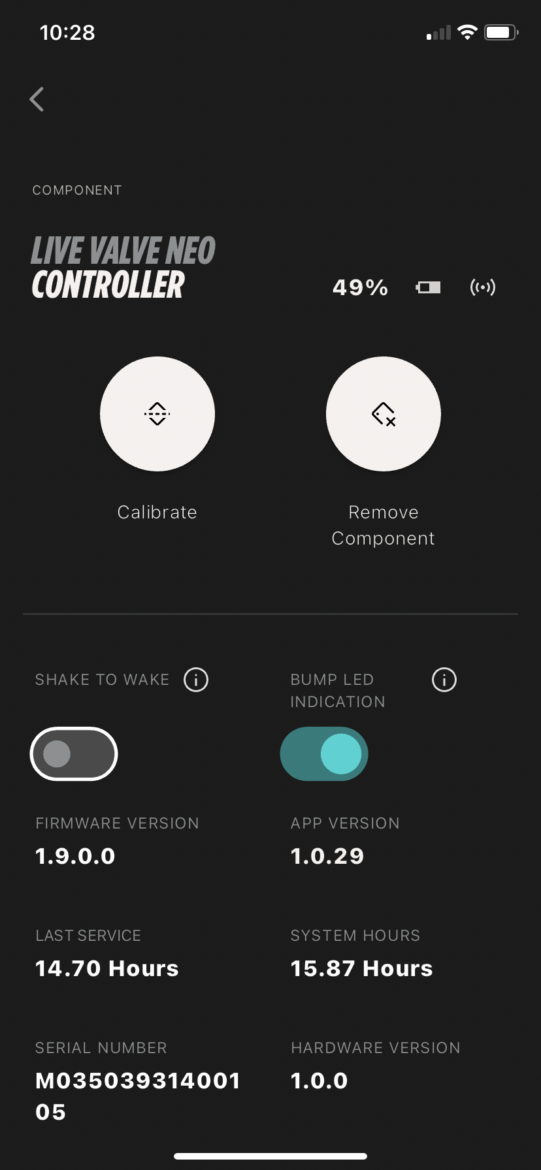

Once the mechanical bits of the shock have been dialed in, now it’s time to get into the Neo app. This is where things get a little more complex. The app allows you to really dig into things, starting with basic setup that includes pairing and calibration. This takes less than a minute or two. Now it’s time to get to grips with tuning things.

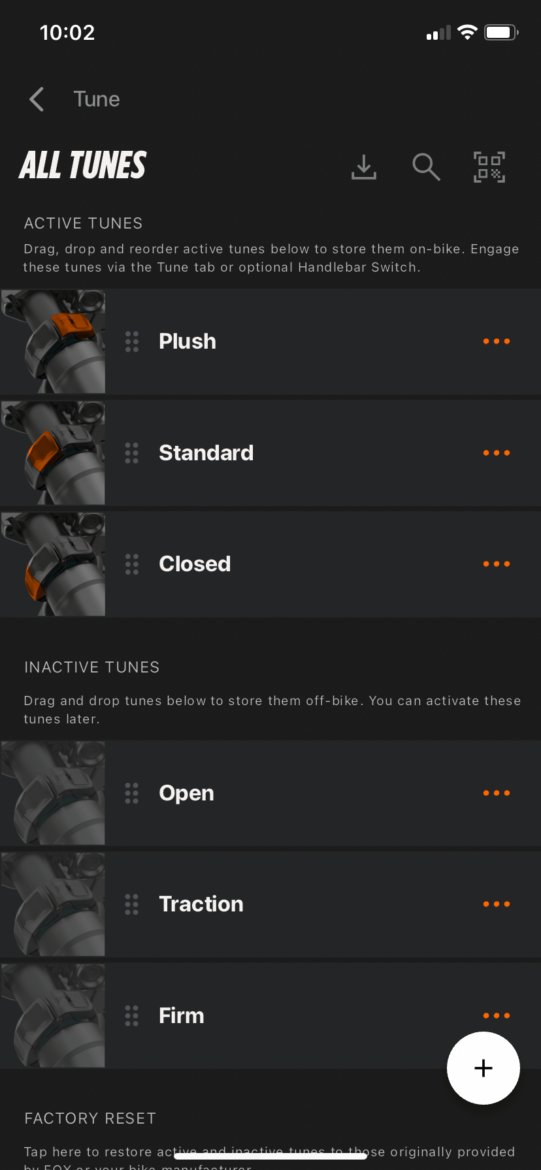

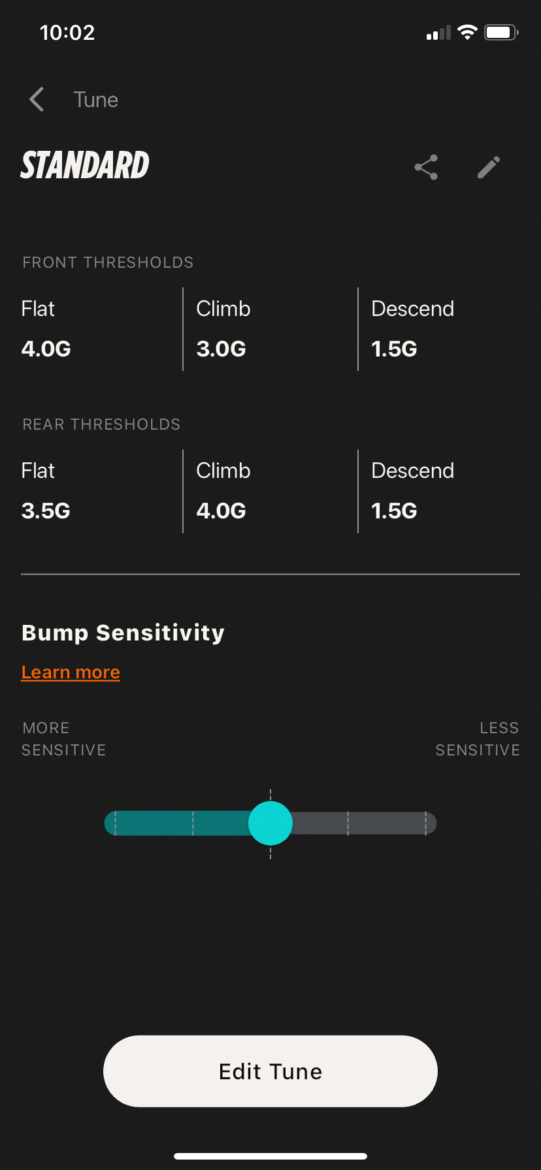

Off the bat, the Neo shock comes with a few pre-loaded tunes that do different things: one is called “standard,” then we have “plush” and “firm,” as well as “open” and “closed” These are all fairly explanatory, but Standard is designed to be their best catch-all tune for most folks. Plush errs toward remaining open more often, and firm does the opposite. Open leaves the shock fully open all the time, and closed makes it fully firm all the time. There are other additional tunes that are downloadable, such as a “Shore Tune,” and users can even create their own tunes.

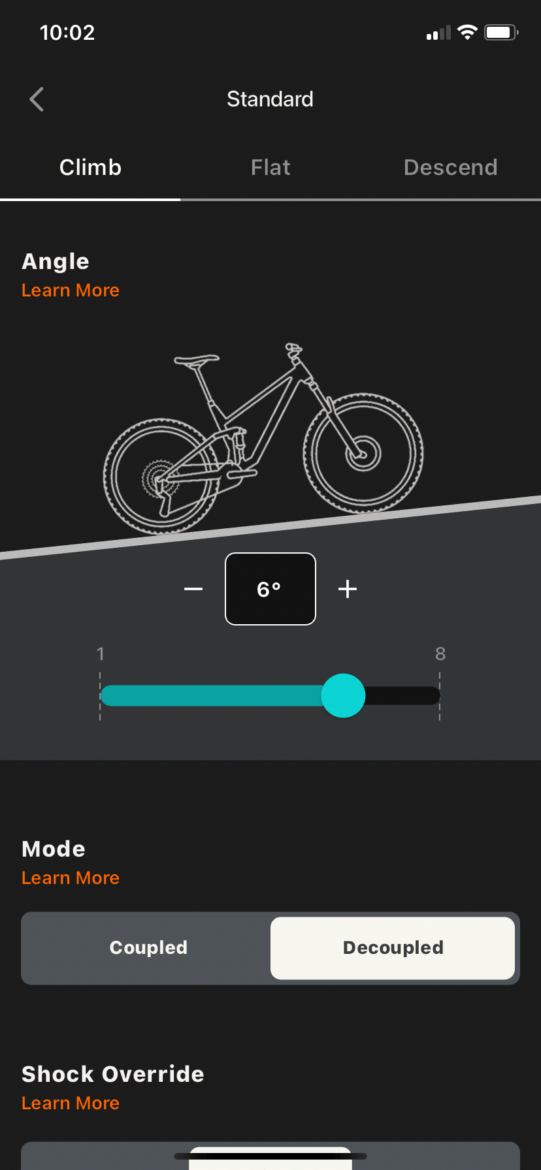

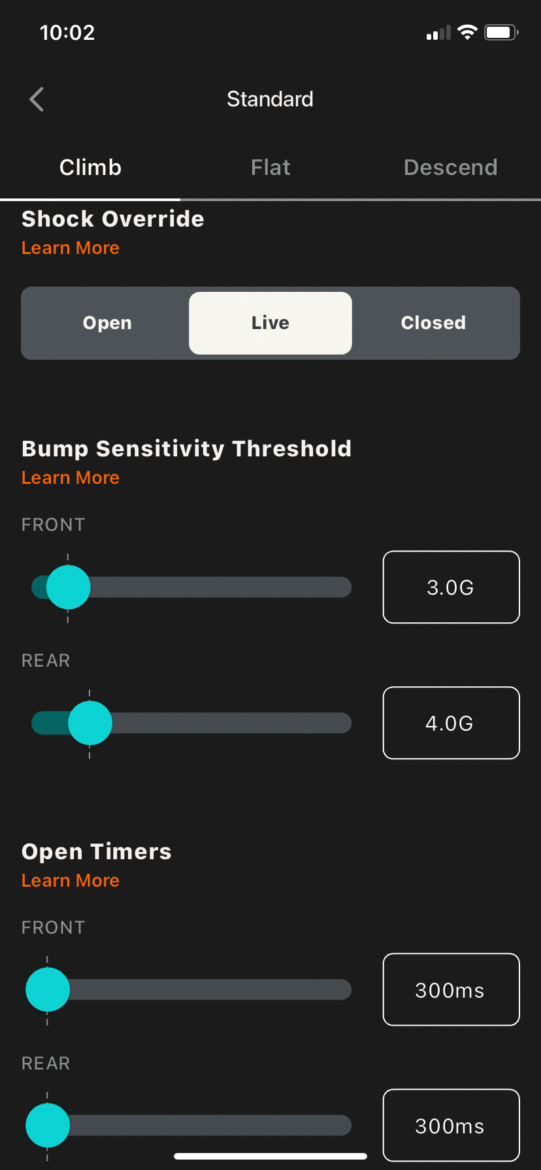

On the most basic level, the tunes split riding into three zones: flat, climb, and descend. They then define the bump force required from either front or rear sensors to flip into open mode. The user can then tune overall bump sensitivity to one of four positions from less sensitive to more sensitive on each tune. Users can even go deeper into the tune to determine things such as the angle required for each zone, bump sensitivity threshold, open mode timers, or select open, live, or closed as an override for each mode. For example, you could set the shock to be always open when it’s determined to be descending, or always closed when climbing.

You can set these modes and change them on the fly while riding if you like, or you can set a tune and forget it — the shock will always default to the last tune loaded. The handlebar switch will allow users to change modes on the fly from the handlebar in the future.

The app also allows the user to monitor battery levels, as well as install firmware updates, check riding hours and service intervals, and book servicing remotely. Smart.

Ride Impressions

I’d like to temper this section with the acknowledgment of my past diatribes regarding electronic components. While I do have a healthy amount of skepticism, my previous writings were also intended to be thought experiments. I am open to trying new things and will form my opinion based on my own experiences. I have yet to try Rockshox Flight Attendant or the first gen Fox Live Valve, so I cannot comment on how either compares to Live Valve Neo.

I’m currently about five rides in on Neo, and have done my best to ride it on trails that I know and can repeat, as well as new trails, with a good mix of flow, tech and gnar. I will say that despite Neo seeming somewhat basic on the surface, there’s a lot to figure out here. My first few rides were spent mainly trying to figure out what tune I wanted to use, and what exactly was happening.

The best place to start seems to be, predictably, ‘standard’ mode. While the system is on, the shock will default to firm mode, so simply sitting on the bike, you’re going to feel the bike in firm, which is an opportune time to tune that mode. I needed a little reassurance that things were working properly, and the best way to do this is to switch between “Open” and “Standard” in the app, to feel it doing its thing on flat ground. If you bounce on the bike aggressively enough you can also feel it open up. The solenoid is extremely quiet, so there are no audible cues while on trail that it’s working; you just have to trust it.

To get a feel of how things work, I first went to the two extremes — closed and open — to feel the bike when it’s in fully open, and fully closed, much like a regular shock with a climb switch. The firm mode is not fully locked, but it does firm up quite a lot. It makes the difference between losing traction on a technical climb or putting power down for sure. Open mode feels exactly how you’d expect it to. For reference, I always leave the shock open on my Tallboy since it’s a fairly efficient climber.

To install the Neo system on my Tallboy I initially thought might be a waste given the pedalling characteristics of the bike, but I was pleasantly surprised. Fox is changing the narrative a little with Live Valve Neo, putting emphasis on how it allows the bike to ride higher in the travel. I’m still getting to grips with things, but initial impressions are that it does indeed ride higher. Setting my Tallboy in the low geometry position that I found resulted in too many pedal strikes before, however with Live Valve doing its thing, it feels more manageable and upright in the climbs. When things get technical, the shock opens up to offer extra traction, which is especially noticeable when tested back to back with the closed tune.

The descents in BC are mostly pretty rough, and I feel like the shock probably spends most of its time in open mode, but it’s worth mentioning that I never entered a rough section and felt like the shock was too firm. I did test a descent back to back in “open” and “standard” tunes, and while I rode it faster the second time around in standard, that could be put down to being more familiar with the trail, trying harder, etc., though I did feel a little extra boost in some of the jumps where the shock firmed up hitting the lip. The extra support on the takeoff of a jump takes some adjustment with regard to front/rear weight bias, and I found myself with my weight pitched forward a few times.

The experience with Neo is honestly pretty seamless however. For the most part, it opens and closes so fast you’d never even know it was happening. It’s been overall positive so far, with my suspension pretty much doing what I want it to most of the time. I’ve somewhat settled on a wide-open low speed compression, and the firm mode two clicks of seven from the firmest, resulting in an efficient ride that doesn’t feel too dissonant when it switches from firm to open. I appreciate not having to think about my suspension settings a whole lot, and while I typically leave my Tallboy’s suspension open 100% of the time when running regular suspension, the performance upgrade is neat, especially on the climbs. Anyone running a bigger bike with more energy to waste would stand to benefit dramatically from the system.

While Live Valve Neo does feel pretty natural to use overall, I have experienced some “notchiness”, mostly when riding on flat, smoother trails or asphalt. I can feel what I think is the shock opening and closing when it can’t quite decide what it wants to do, or perhaps it’s the feeling the shock produces when the bump force isn’t significant enough to open the damper. Stay tuned on this one.

Summary

Overall my first experience with Live Valve Neo has been quite positive. It seems to do what it claims to. I’m not much of a fiddler when it comes to suspension settings, and I’ll probably get to a point where I set and forget it, at which point I’ll have something that provides meaningful performance gains while allowing me to truly set-and-forget, so long as I remember to charge the battery. So far it’s allowed me to utilize the low-geo mode on my Tallboy, unlocking extra descending performance. I could also see people dialing in a plusher sag setting because it typically rides higher, again unlocking a more forgiving descent, while also increasing efficiency when it comes to pumping/jumping. The benefits on the climb are obvious, but I’ll spell it out: increased efficiency, fewer pedal strikes, more traction when it matters.

There are, of course, downsides. With extra complexity comes, well, extra complexity: three more batteries to charge/replace, electronics that might fail, and more setup time. As with all things Bluetooth, the app doesn’t connect to the shock the first time every time, and has required some restarting of devices to work, but it has been pretty good overall. Battery life is okay — you can switch between “shake to wake” or not, which turns on whenever it detects a bump and stays on for an undetermined amount of time. Since the shock uses power any time that it’s on, it’s probably best to manually turn it on/off. Even so, the battery life isn’t the best, using 36% on a recent four-hour ride, giving it an approximate total of 12 hours riding time. That’s not a ton, and a single big day in the saddle could wipe that out.

Oh, and did I mention the price? You’re looking at $399USD for the Neo kit including bump sensors, battery, charger, and cable. Plus $999USD for a Neo Float X shock or $949USD for Neo DHX shock. That’s a lot of coin.

Finally, I think the lack of any telemetry in the app is a bit of a missed opportunity, and maybe that’ll come. I think Fox could really build in some extra value and functionality for the rider if they were to include some ride analysis, similar to Quark Shock Wiz for example, so people can really make the most of their setup, for example, number of big compression events, air time, and tuning tips based on those events.

I don’t think Live Valve Neo is necessarily for your average rider, and it’s not really meant to be. For the all-in rider with expendable income that truly wants to get the most out of their high-end bike, Neo is a performance benefit for sure, and worth the money. I think where Neo also makes a lot of sense is for racers — it would have been invaluable for me during BC Bike Race where every ounce of energy counts. I could also see this working well for enduro racing, where any wasted energy during a descent is lost time, and a quick switch into firm mode for a mid-stage pinch climb might make the difference between taking a stage win or not.

Pros:

- Easy setup, minimally intrusive aesthetics

- Super fast switching between open/firm, feels very natural

- True set-and-forget riding, once you get it dialed

- Genuine performance benefits whether pointed up, down, or in between

Cons:

- Expensive

- Occasional notchy feeling on flat ground (could be setup related)

- Battery life could be better

- No built-in telemetry

2 Comments

Sep 24, 2024

Also, your estimate of 12 hours on one charge is surprisingly short. As you noted, the system defaulting to "open" is reassuring, but these batteries sound like they'll take MUCH more charging than the derailleurs and dropper posts.

Sep 24, 2024

I do agree re: the battery life though. Most people aren't doing four hour rides every day, but I think it will take more charging than an AXS derailleur, the one positive though being that the bike is perfectly rideable should the battery die.