Tires are the one and only contact point between your bike and the trail surface. They’re arguably one of the most important, if not the most important, parts of your bike. All that hard work you put in on the climb isn’t possible unless the tires are on the ground, and neither is that line through that rock garden.

You just can’t ride a bike without tires, and should the air decide to leave your tires mid-ride, the ride is over unless you have a way of getting air back in there. I think I’ve made my point here — tires and the air inside them are unmistakably important.

In my quest to understand the most important innovations over the last decade or so that make modern mountain bikes the amazing machines they are, I previously spoke to a bunch of folks about 1x drivetrains and the impact they have had on mountain biking. The consensus was that while it was major, it wasn’t necessarily what they would call ‘innovation’ in the real sense of the word since it was a gradual change in existing technology that allowed us to optimize other parts of the bike. However, one thing that was mentioned a couple of times was tires and so here we are.

In researching the previous article Noel Buckley, the founder Knolly Bikes, told me that the removal of the front derailleur allowed bikes to run bigger tires, and that tire compounds are one of the biggest and best things to have happened to modern bikes. With that in mind, we reached out to more industry professionals for their opinion on how tires have evolved.

Starting on the surface

One of the first and most recognizable changes tires have seen are in tread patterns. A far cry from classic tires of years gone by like the Onza Porcupine and the Panaracer Smoke and Dart, tread patterns are much more nuanced than those days when shapes were simple. The treads were, for the most part, symmetrical front and back. For example, the leading edge of a knob was the same as the trailing edge and tread depth probably did most of the work.

Ken Avery, the senior vice president of product development and marketing of Vittoria Tires explained that when designing a tread pattern, he looks at how the tire behaves from all angles and whether cornering, braking, or accelerating, not only is he looking for grip, but also debris ejection channels so the tire can continue to grip rather than clog.

Avery said he designs his tires so that he creates benefits with as few drawbacks as possible. For example, the Terreno Dry tire has a ramped “fish scale” pattern down the center tread which rolls like a slick but under braking the backs of those scales dig in like velcro and create a ton of braking grip on hardpack. For the same reason, a tire like the Martello has a ramp on the front edge of the tread for climbing efficiency but a square edge on the back for braking grip.

Avery further explained how Vittoria has employed “progressive sipe width” on their tires where the sipes (the small gaps carved into the knobs themselves) are progressively wider or narrower so that they can tune the support or suppleness of a knob without changing the rubber compound.

For example, the inside edge of a side knob on a Martello has wider sipes for more grip but they firm up toward the outer edge for support when cornering. The center knobs are the same but turned 90° to provide a firm edge for climbing efficiency but a softer edge for braking to prevent the brakes locking up on slippery surfaces, without using an overly soft rubber compound.

We’ve seen similar changes from brands like Maxxis in tires such as the Assegai and Dissector, where Maxxis created tread patterns that combine good rolling properties with great mud shedding and grip.

Aaron Chamberlain from Maxxis told me how tires such as the Minion DHRII have been totally overhauled to what we have now, where they admittedly were quite off on the original and borrowed the side knobs from a Minion DHF for the new tire. They clearly focused on using that paddle type design at the center for climbing traction, but added a fairly aggressive ramp to improve rolling resistance. The DHR went from something that nobody used—not even sponsored athletes—to something that owns the market space for rear tires now.

Now, Chamberlain said, that Maxxis little to no plans to change such a ubiquitous tire, and if they were, they would likely keep the old tire as some type of ‘classic’ version. The DHF is an example of how some things haven’t changed; it’s a tire that’s existed in Maxxis’ lineup for more than twenty years and is still a serious contender as a solid mixed-conditions tire. Why fix what ain’t broken?

Rubber recipes

Compounds are another important part of the tire, and like tread patterns, some things have changed wildly and some haven’t. The formulation of rubber compounds is something of a dark art of mixing things like natural and/or synthetic rubbers, silica, and other materials, however some companies are more open to sharing what they use in their compounds than others. Vittoria quite openly tells us that their new compounds contain superconductor graphene, yet other companies such as Maxxis and Continental are more cagey and simply use flashy but proprietary names for their compounds.

Rubber compounds vary in softness, known as a material’s durometer rating, and they also have different rebound speeds and other properties. It stands to reason that a softer rubber compound will wear faster and roll slower because it wants to stick to the ground.

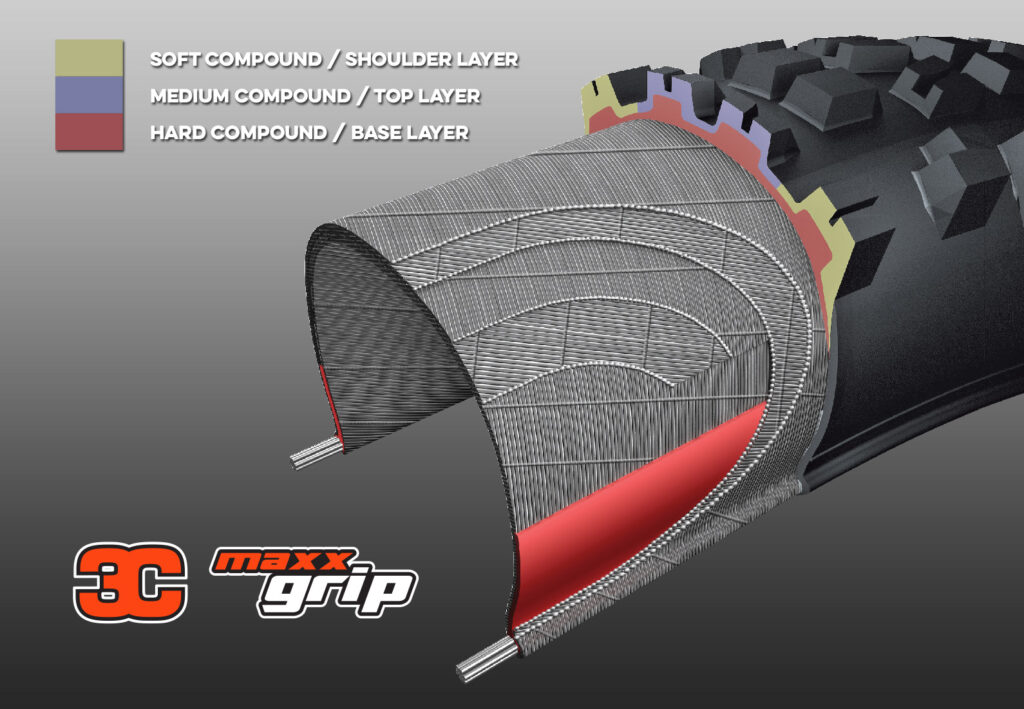

Chamberlain at Maxxis said they really haven’t changed their rubber compounds in a long time and that their 3C Triple Compound has been around for the better part of 20 years. That may be because Maxxis felt they got things right the first time, and don’t need to change much.

Avery from Vittoria on the other hand told me how in the last few years they started using graphene in their rubber compound which in layman’s terms, changes the elastomeric properties of the rubber. Where in the past it was “grip, rolling speed, and durability—pick two,” the addition of graphene not only increases wet weather grip but simultaneously lowers rolling resistance and increases durability. So according to Vittoria, the material allows riders to have their cake and eat it too.

As mentioned above, Maxxis has used their triple compound technology for some time now, but Avery said that Vittoria have the only 4-compound tire extruder in the world. This means that they are able to extrude two layers and compounds of rubber on top of one another on both the side and the center tread for a total of four different rubber compounds, enabling them to finely tune the way the tire handles and grips.

Construction and casing

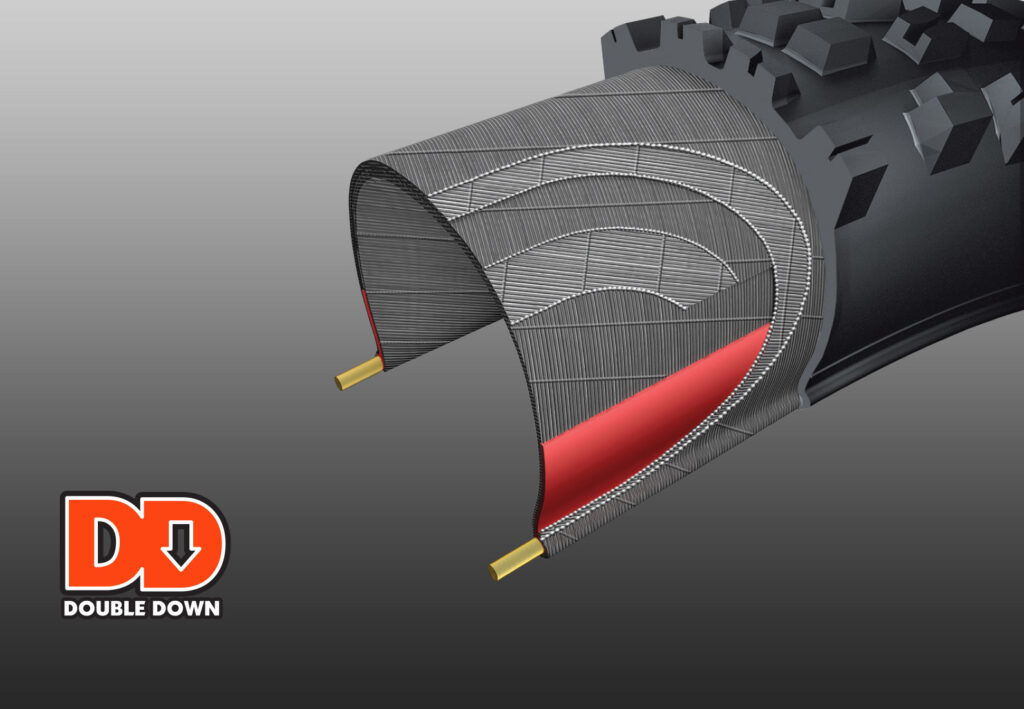

Tire construction is another vital part of the way the tire functions—a thin, lightweight casing can be super fast and ideal for cross-country racing, but a heavier casing can be ideal for downhill where weight is not such an issue and puncture protection is key. For the longest time, not much existed between simple single-ply casings and heavy dual-ply downhill casings. A dual-ply tire weighs about as much as two tires and has a profound effect on handling and efficiency, so anyone that wanted to enjoy pedaling had to put up with thin tires that punctured constantly.

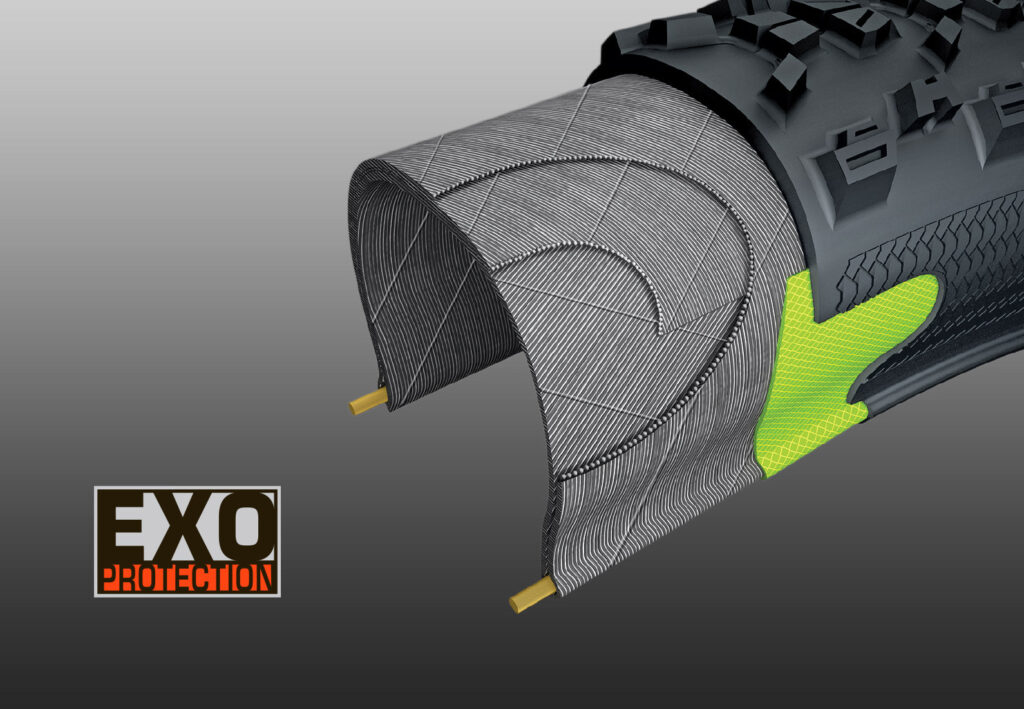

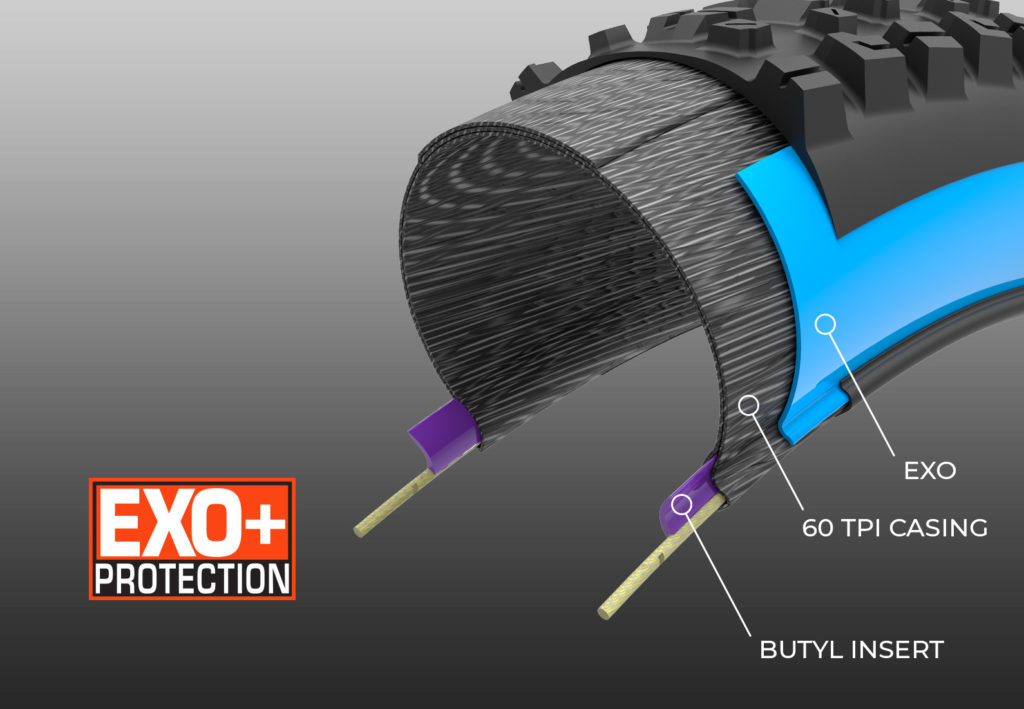

Around 15-20 years ago, companies like Maxxis started introducing new materials into the layers of their tires such as their SilkShield and other protective layers to produce tires that have more puncture resistance while staying lightweight and retaining the compliant nature of a single-ply tire. In the last 10ish years, Maxxis has released multiple casing options between single ply and dual ply with EXO, EXO+ and Double Down, each of which is a little tougher and heavier, but with sweet spots for certain types of riders which balance puncture resistance and rolling resistance to acceptable levels depending on the type of riding.

Chamberlain said that EXO+ was recently updated last year and for a relatively lightweight casing, can brag impressive puncture resistance. I’ve personally become a big fan. Maxxis snuck this one out relatively quietly but it just goes to show that whether or not we know it, these big brands are still innovating and improving rather than resting on their laurels. Other brands have started including things such as bead protection strips to prevent the tire casing from splitting at the bead in the event of a large impact, like a pinch flat. We’ve seen this technology from manufacturers such as Delium, Vittoria, and Continental, to pretty good effect.

Tubeless

While Chamberlain seemed humble considering Maxxis’ position in the mountain bike tire market, he pointed out that the proliferation of tubeless technology is probably the biggest single tire innovation that’s occurred in recent memory. For anyone fortunate enough to be a recent convert to mountain biking, in pre-tubeless times, punctures were fairly common. I remember my university days back in North Wales, where the trails were made of incredibly sharp slate, slashing tires and popping tubes three or four times in one ride. That’s one thing I don’t miss about those days; punctures for me are now few and far between, and I credit much of that to tubeless tires.

Explaining how UST was one of the first tubeless systems invented by Mavic, Chamberlain said that it was designed to be run without sealant, which required a lot more rubber in the tire making them pretty damn heavy. Subsequent attempts at tubeless could be a bit of a crapshoot as to whether or not they would work reliably, but Stan’s No Tubes nailed it. The current agreed-upon tubeless system is universally reliable now, with most rim and tire combos working together the majority of the time. Small punctures and leaks have pretty much become a thing of the past.

Avery also agreed that tubeless moved things forward, as have tire inserts. Not only does sealant seal most small leaks but with inserts such as CushCore or Vittoria’s Air Liner, pinch flats are almost a thing of the past. Another advantage of inserts is the way they ‘deaden’ the tire making them less bouncy and more damped, which should in theory lead to more grip. They have also opened the opportunity to run lower pressures for better grip and compliance with a lower likelihood of punctures.

I’ve got to say I agree, and since moving to tubeless with inserts, I can count the number of punctures I get in a year on a single hand. It’s pretty impressive and with tubeless tires, inserts, and 1x drivetrains, the problems and interruptions of the past—dropped chains and flats—have allowed myself and others to spend more time riding and less time wrenching trailside.

Chamberlain said the main change in aiding tubeless has been to the bead profile, but otherwise there haven’t been big technological leaps to tires in recent years. While what I was trying to understand through him is how far we’ve come, the changes are mostly still simple and gradual.

Convergence in designs over the years and cooperation between rim and tire manufacturers for agreed-upon standards created an improved overall system. This leads me to think that one of the most important and influential new technologies in mountain biking in the past decade is actually the tubeless innovators. Stan’s No Tubes, what do you think?

5 Comments

Mar 6, 2023

Mar 7, 2023

Mar 6, 2023

That's my experience at least.

Mar 7, 2023

Summer alone sets me back 3 pair of tires, I can deal with it vs. tires that slip n slide like a greased pig on ice.

75kg for a light riding style I possess, low durometer, please!

Needless to say, it's good to hear what the tire makers are up to and working on.

Mar 9, 2023

What feels a million years ago, I wrote this opinion about this...

What's next after tubless-ready, 29er wheels.