First things first, we’ll jump to your foremost burning question. Like most good branding, the name Bluegrass Eagle came up in an early meeting and the team liked the sound of it. There’s no deeper significance, nor connection to the music genre. They are, however, looking for a good pickin’ band to sponsor if you know of worthy banjo or fiddle slingers. The owners wanted to clearly distinguish Bluegrass from their more road-focused brand called MET. In case it’s not obvious, the name for that one is simply short for helmet.

Last month I was invited to the Bluegrass and MET headquarters in Italy’s Valtellina Valley to learn a little about how they develop helmets, and to ride some trails in the area. The steep valley walls around the office are as covered in singletrack as anywhere in northern Italy, and the trails are well worth the drive from a nearby airport. You’ll find a lot of local riders on e-bikes or shuttling, as the smooth climbs last well over an hour and the descents are undoubtedly worth the work.

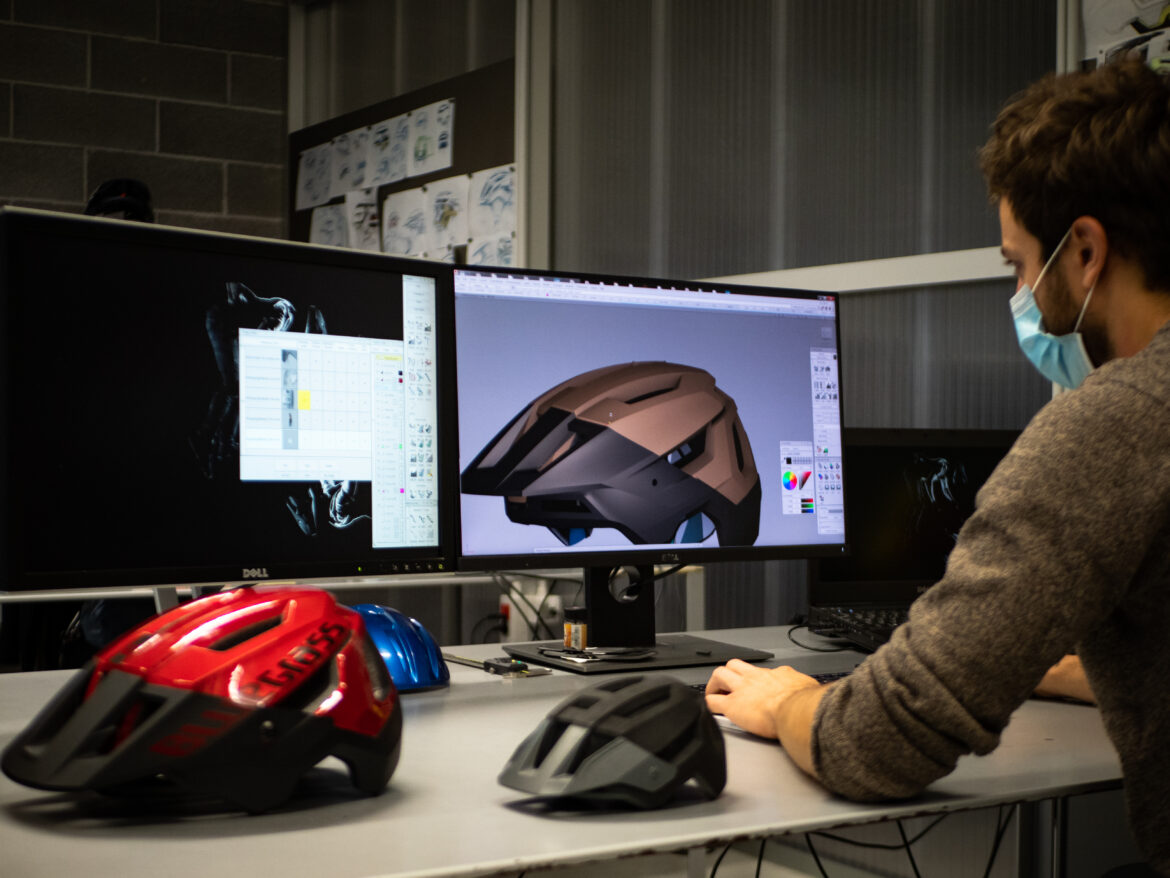

The multi-faceted design process for a new helmet model often lasts more than a year, and it all begins with multiple hand drawings and software illustrations. Once the general internal and external shapes are determined, the engineers create clay models and 3D-printed renditions to have a better feel for how the product might look and feel. They fine-tune every millimeter of those designs to ensure proper functionality, airflow, fit, and form. From there the design moves on to impact modeling to determine if its thicknesses and structural fortification meet the Bluegrass requirements and the laws that govern the larger protection industry.

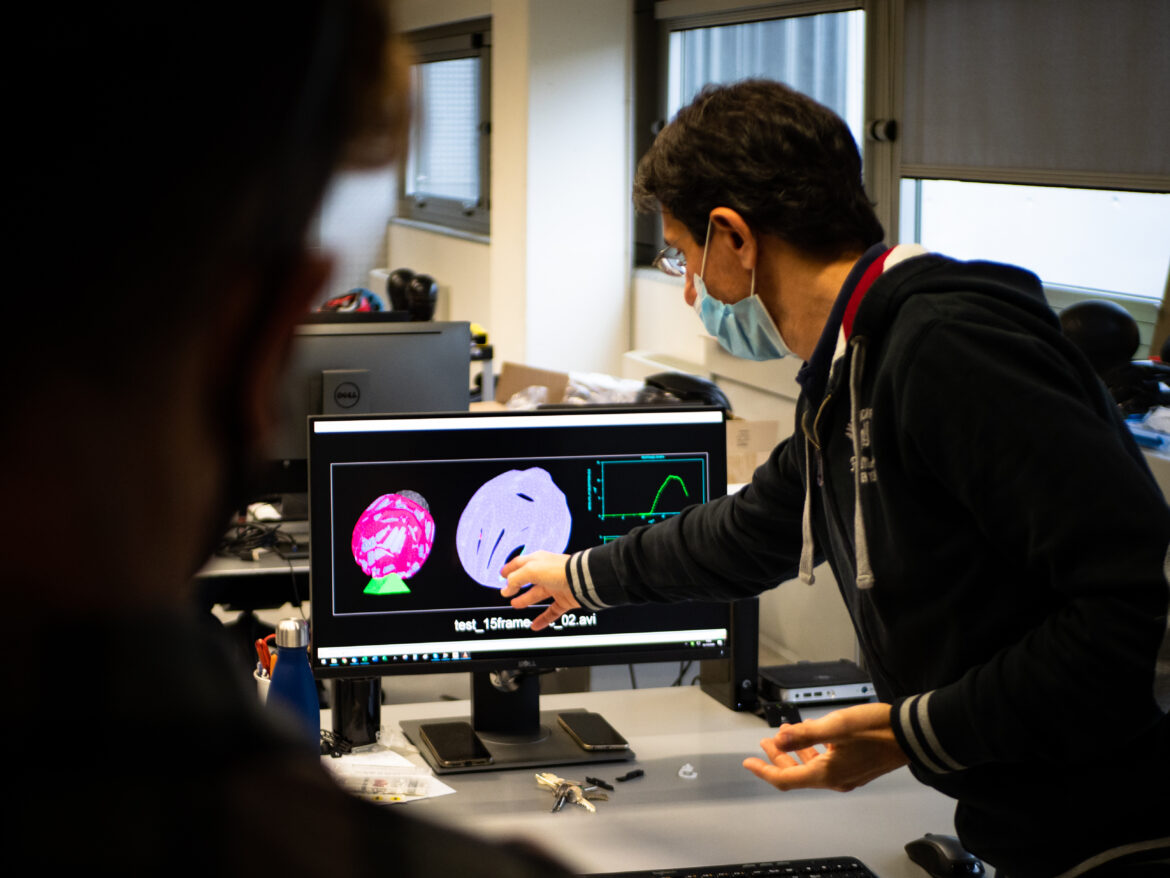

The next step is to test the design with software simulations that can determine how well each piece of the helmet protects the rider’s head on impact. There are strict parameters each design has to meet before it can go on to the prototype phase, including metrics that show its ability to dissipate energy throughout the shell rather than transferring it to the rider’s head. These tests are intentionally thorough, and all of the engineers work together to refine the design until it’s as safe as possible. Then, the exterior elements like the MIPS layer and chin strap are added and refined, and the design is sent off to be prototyped.

The initial models are made in the Bluegrass factory in China, where the company has employees regularly checking the production process and quality throughout. They are able to make changes as needed and to work with the skilled team at the factory to create a product that meets their specific standards.

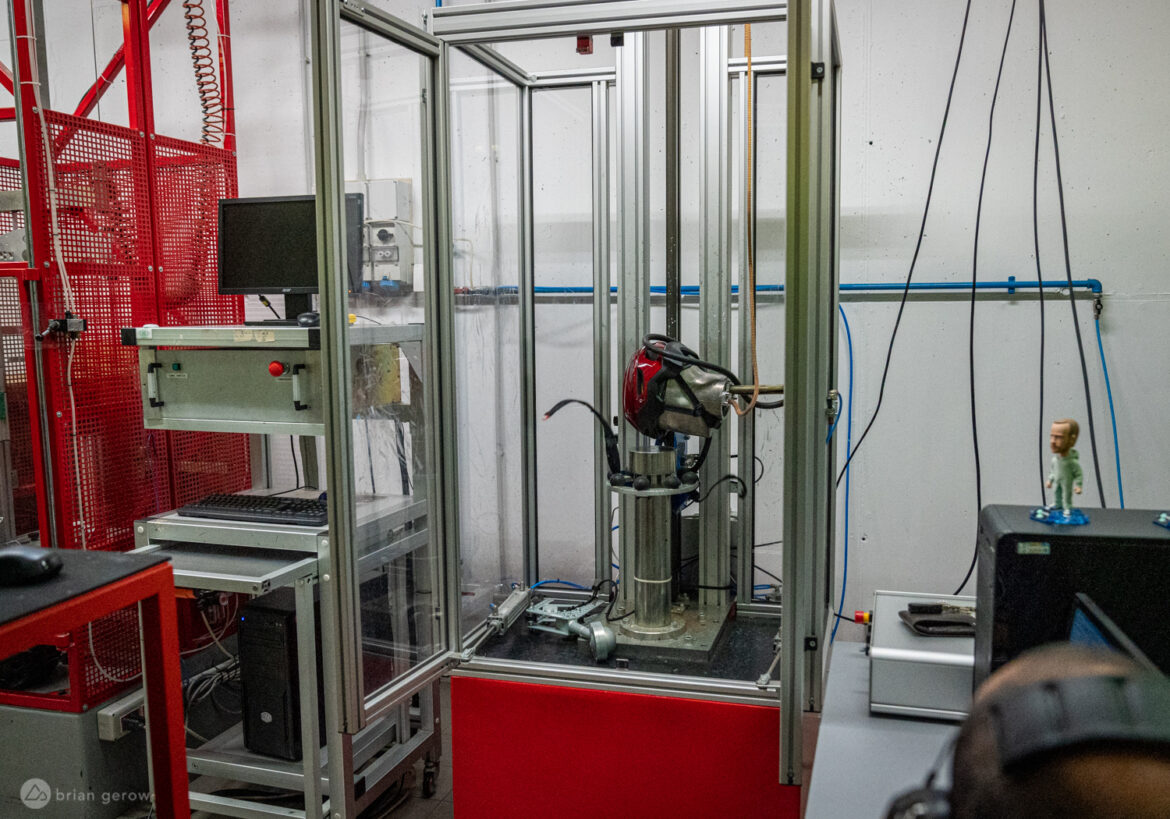

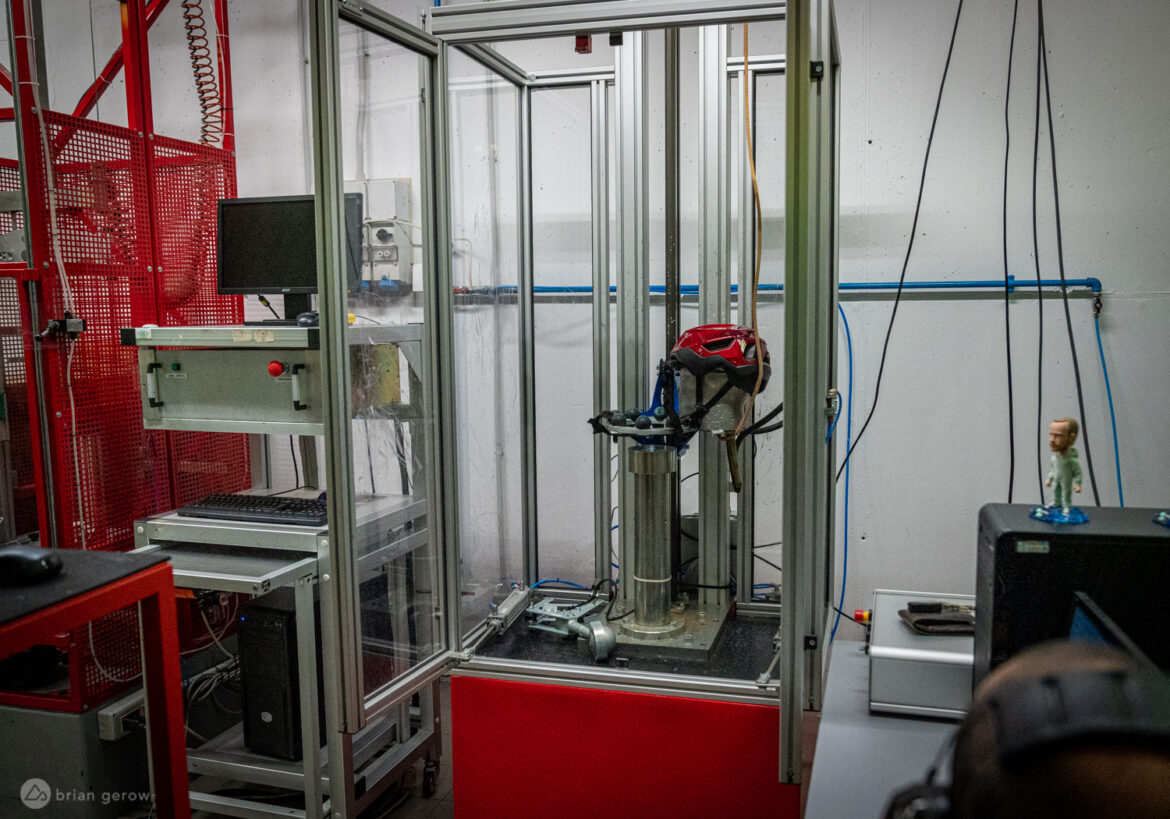

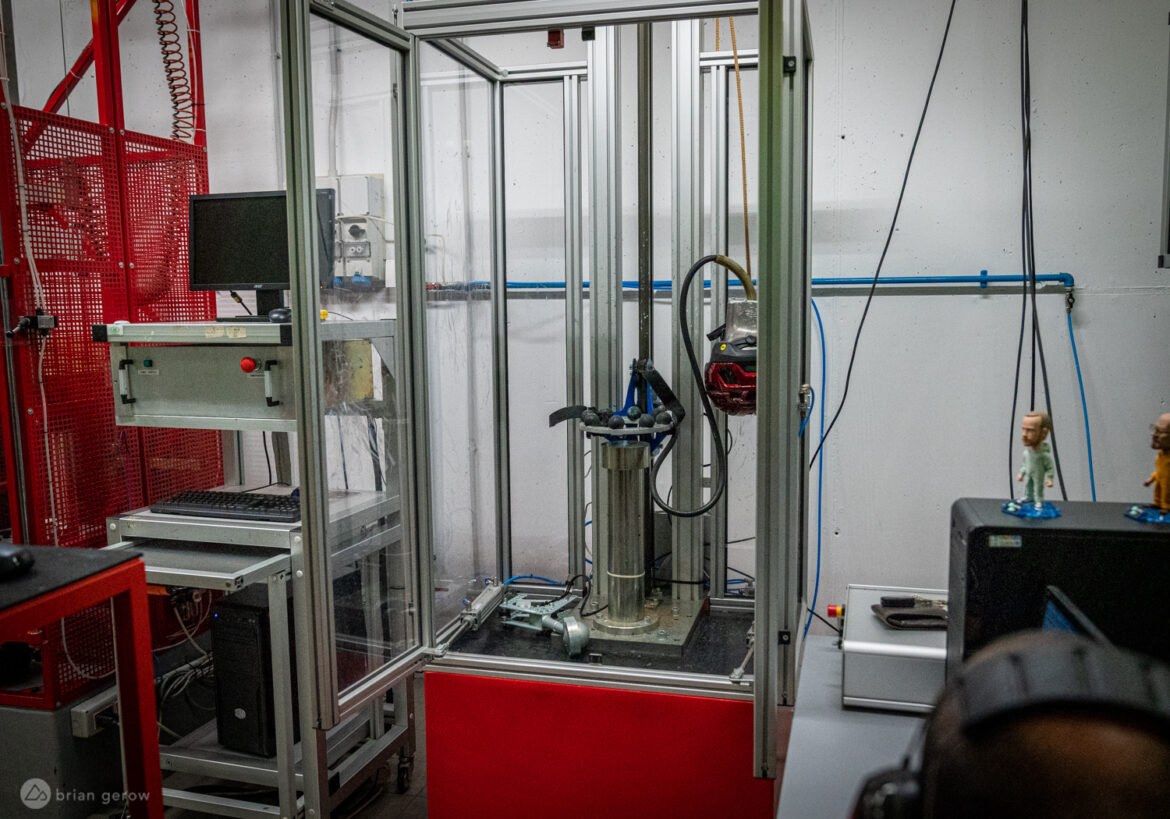

With prototypes in hand, riders go out and test them on the trail to evaluate the fit and functionality of the new model, assuring that the design is optimized for real world activity. In addition to the human testing, each model goes through hundreds of machine-driven crash tests in the Bluegrass lab to see how it holds up and to check for any safety flaws in the design or production. Bluegrass is one of very few helmet manufacturers in the world to have all of the testing equipment for international helmet certifications in house. For the Rogue alone they broke over 700 helmets before putting the product on the market, refining pieces of the design and making sure our heads will be safe.

The machine above is one of many in the Bluegrass lab that throws weighted helmets into hard objects, using a variety of gages to measure energy transfer on impact. They run the impact tests with the helmets wet and dry, and in a variety of extreme temperatures, to determine how the materials change and if their protection properties are affected.

Once the lab experts are satisfied, a set of new helmets is sent to external test centers for official certification. When the model is available for purchase, Bluegrass tests a handful of helmets from each batch to make sure there were no production errors. A specified number of new helmets from each batch, in all sizes, has to be kept on hand at the Italian office in case there is an issue with the batch.

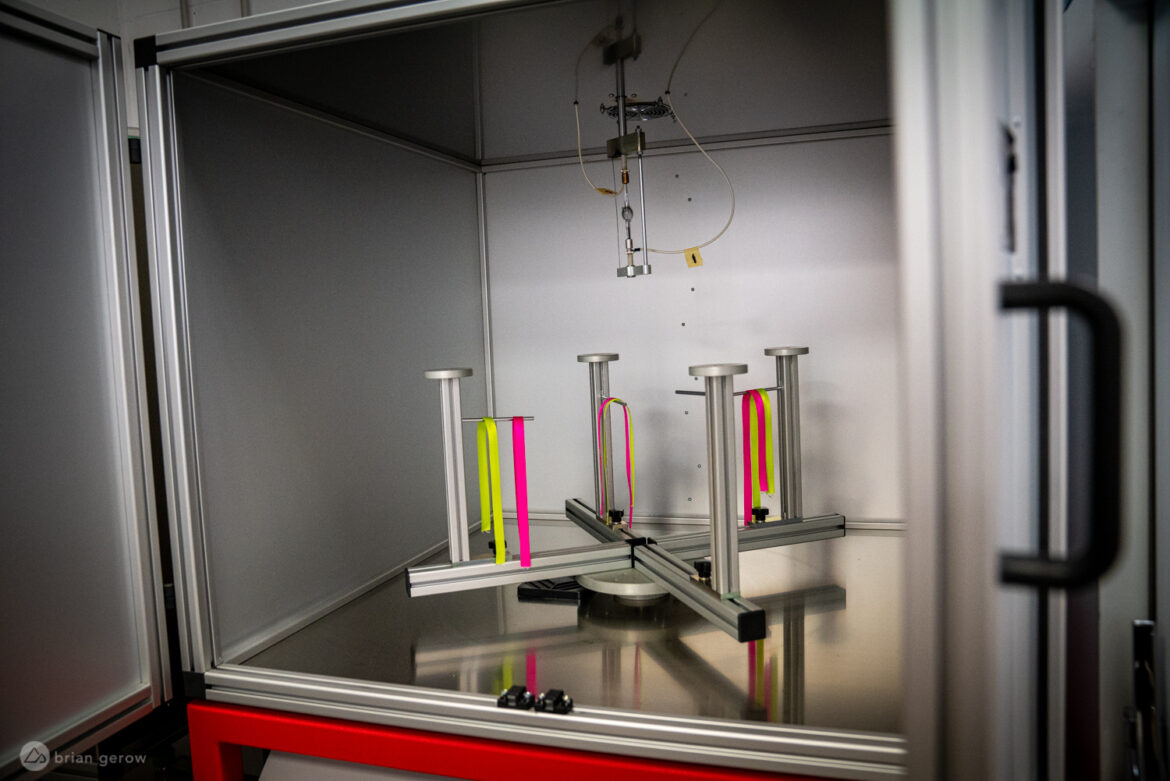

In addition to impact testing, the helmets and all of the pieces that attach to them are run through UV and hydro testing to see if the materials will fade or degrade in the Arizona sun and how well they will hold up to a bleak Scottish winter. Highlighter hues like the pink and yellow in the above photo fade the fastest in the UV tank.

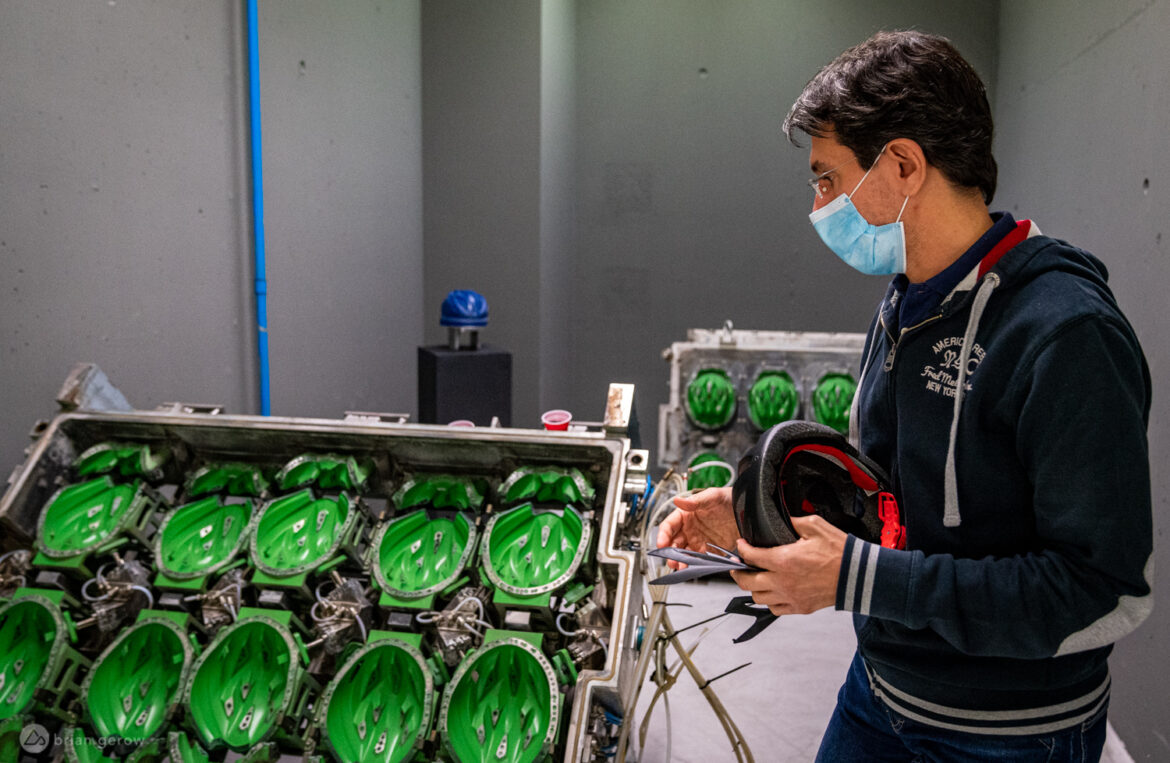

MET and Bluegrass helmet production originally took place at their headquarters in Talamona, Italy, and this was one of the machines that pressed Expanded Polystyrene Products (EPS) into the shells.

As with nearly everything, the price of goods and labor drove helmet production overseas, and the original helmet factory will eventually be turned into an indoor pump track and bike skills park.

I asked the engineers at Bluegrass how they test light and camera mounting on helmets, and the answer made the question feel a little silly. They can’t. There is no way to know what a customer will mount on their helmet, and where they might put it, leaving them no meaningful way of evaluating the effects of accessories on their helmets. For example, even if they provided a specific mounting position on the shell, they would have no control over what people choose to attach to their heads. This is the same reason that the UCI governing body (Union Cyclists Internationale) only permits athletes to attach cameras to the visor of their helmet in their sanctioned races. Visors are designed to come off easily on impact, not affecting the direction or protection of the helmet itself.

That’s all from our factory tour. Here’s a quick photo gallery shot by talented Bluegrass Marketing representative Ulysse Daessle, of Liam Moynihan and I riding some trails near HQ. Liam is a decidedly more stylish helmet model than myself.

Thanks Bluegrass!

0 Comments